A rapid growth sector, historically undervalued

The care and support economy is a significant contributor to employment, economic growth and societal well-being in Australia. Yet, care and support work has not traditionally been considered by governments through an economic policy lens, resulting in its associated economic benefits often being neglected. We also don’t capture the value of the unpaid labour that takes place, overwhelmingly performed by women, within households in our Gross Domestic Product. This means the socio-economic value of this unpaid care to the Australian economy is not always visible and appreciated.

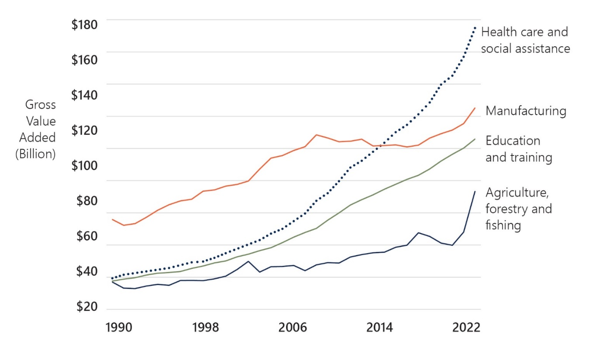

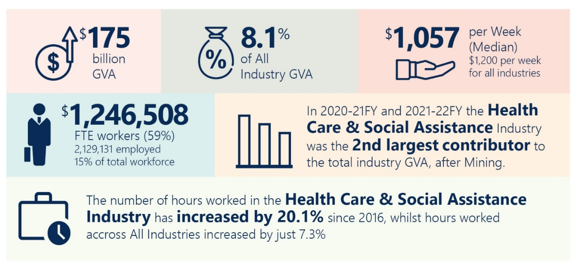

Over the last 70 years, the structure of the Australian economy has changed significantly. There has been a rapid growth in the service sector, both in terms of output and employment. Over the past 35 years Australia has seen a significant increase in government subsidised and ‘non-market’5 services – in particular health care and social assistance.6 This growth has far eclipsed the growth in ‘traditional’ industries such as manufacturing. The health care and social assistance industry now accounts for 15 per cent of Australia’s workforce, making it the largest employing industry in Australia. It is forecast to grow faster than any other industry. 7, 8

An economy connected to equality and inclusivity

The care and support economy matters for gender equality, socio-economic equality, poverty reduction, inclusive growth and sustainable development. Higher income households often have greater ability to access a combination of paid professional, institutional and informal family care and support. Conversely, lower-income households are often limited to informal family care or insufficient care and support.

Government investment in care and support can deliver both social and economic returns.

For First Nations people, providing care and support for community members often falls within expected kinship responsibilities and cultural obligations. This leads to a high burden of unpaid care, economic exclusion and underutilised service delivery avenues.

First Nations carers are more likely to be unpaid carers for a person with disability than non-Indigenous Australians.10 First Nations carers and their families, especially those in regional and remote areas, experience severe financial distress and often have to forgo essential items such as nutritious food to cover the costs of daily living.11 Overwhelmingly, research describes desires among First Nations people for more support for caregiving within families.12

Lack of access to much needed care and support services also shapes the household labour supply structure. For instance, it may be easier for both members of a couple with a higher family income to work given they can afford alternatives to unpaid care. In contrast, research highlights that the lack of affordable ECEC is a significant barrier particularly for women in low-income households which can prevent them from entering the workforce.13 These households tend to be more vulnerable to economic shocks and at a higher risk of poverty. Overall, expansion of care and support services can facilitate dual earner households, reducing the risk of income poverty.

The care and support economy is growing, driven by an ageing population, a transition from informal to formal care, and increased citizen expectations of government. The most recent Intergenerational Report projected the share of the population aged over 65 years old will increase to nearly 23 per cent as the baby boomer generation ages over the next 40 years.15 This will drive the dependency ratio — the ratio of working age people to non-working age people — down by almost one-third (from 4 working-aged people today to around 2.7 people in 2060).16 In addition, demand for ECEC services is also likely to increase and at least keep pace with working age population growth, consistent with higher labour force participation of women.

Productivity growth is crucial to fulfil growing demand for care and support services

The care and support workforce is growing 3 times faster than other sectors in the Australian economy. With demand for care and support services expected to outstrip workforce supply, the previous National Skills Commission projected a workforce gap.17 By 2049-50, the total demand for care and support workers is expected to be double what we see today.

Given the increasing demand for workers and the shrinking supply of working age people, productivity growth is becoming increasingly important. Stronger productivity growth within the care and support economy could contribute to lowering future workforce demand. Plus, from a workforce supply perspective, stronger productivity growth across the economy as a whole could increase the potential share of workers available to work in the care and support system.

Australia’s productivity growth has been in decline over the last two decades. The recent 5-year inquiry from the Productivity Commission reports productivity growth of close to zero in the non‑market sector since the turn of the millennium.18

As the care and support economy continues to grow and comprise an increasing share of the national economy, productivity growth in this system will be fundamental to lifting our overall national productivity. We should seek to understand what might be hindering productivity growth in the services sector and, where there is strong evidence for cost-effective intervention, we should act.

Government expenditure in care and support services is an investment in social infrastructure

Social infrastructure is the facilities, spaces, networks and services that support quality of life and wellbeing in our communities, and it includes education, care and health provision.

Poor understanding of the economic and social impacts of care and support systems mean we can undervalue social infrastructure in investment decisions.

Public funding of high-quality care and support provision is an investment in social infrastructure. It provides long-term benefits (returns) as well as wider public benefits that accrue beyond the direct users (infrastructure).

Care and support work, both paid and unpaid, has generally been seen as low prestige work in Australian society. These biases impact how care and support work is valued, compensated and recognised. Consider how differently we measure spending on physical infrastructure (as an investment) and social infrastructure (as an expense, despite its potential for significant long-term fiscal and economic and social dividends). Ultimately, this distinction impacts the allocation of resources and the overall quality of services in the care and support economy.

The Australian Government’s forthcoming Measuring What Matters Statement—Australia’s first national framework on wellbeing—will provide a better picture of whether policies are working and support more informed discussions about what needs to be done to improve the lives of all Australians.

Investing in social infrastructure brings economic benefits

Investing in social infrastructure helps improve productivity in other economic sectors. It also brings greater development opportunities for children and increased women’s workforce participation.

Investments in the care and support economy support greater returns on our human capital. For instance, ECEC impacts the physical, social, and mental development of children, ultimately better equipping them to succeed in school and adult life. Moreover, it is critical to note that that over half of NDIS participants are younger than 18, and over 15 per cent are younger than 7. 19

This investment, therefore, has a number of potential long-term benefits, both for the individual and Australia as a society.

Access to care and support services can boost labour force participation

Access to care and support services supports greater labour force participation of the people providing unpaid care, predominantly women. It also boosts their productivity and improves their work-life balance.

Helping those with caring responsibilities access care and support services improves this group’s availability to undertake paid employment. In 2021, caring responsibilities affected the labour force participation for over 900,000 people.20 Of those people, over 80 per cent were women. The data showed 45 per cent of them wanted to work but could not.

Access to care and support services can also help the people providing unpaid care to increase the hours of their paid work. In 2020, the Productivity Commission reported that employed carers who provided care for 30 or more hours per week worked 3.2 fewer hours on average than people who do not provide care. These pools of potential workers represent an untapped workforce supply.21

Reducing unemployment and underemployment in this group would also ease the pressure on public expenditure. Newly employed people would pay tax, and fewer social security payments would be made. In the longer‑term, there will be returns from the care and support investments themselves. For instance, investing in comprehensive care and support (including preventative care) for older adults can result in reduced healthcare costs, improve quality of life and increase social cohesion within communities.

How care and support investment assists women’s economic equality

The impact of the care and support economy on women is two-fold.

Firstly, it is widely recognised that women perform a disproportionate share of unpaid work, including care and support for those who need it. This gender imbalance in the distribution of unpaid care work constitutes a root cause of women’s economic and social disempowerment. Care and family responsibilities (unpaid care) and industrial gender segregation (of paid care and support) account for 53 per cent of the gender pay gap in lifetime earnings and superannuation balances.22

Achieving gender equality is a priority action for the Australian Government. It is important socially and economically. The Government will release a National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality in the second half of 2023, guiding whole-of-community action to help make Australia one of the best places in the world for equality between women and men. It is an important mechanism to elevate and prioritise actions that will achieve gender equality.

Public funding of care and support services can alter the distribution of work in society and provide women with economic autonomy: they free up women to participate in the broader workforce.

Secondly, the care and support economy is gender segregated, meaning that there is an unequal distribution of men and women. Female-dominated industries are marked by low pay, poor bargaining power, economic insecurity and high flexibility.23 Gender segregation in care and support is driven by historic norms of care being performed within households, by women.

Gendered undervaluation of women’s work is a widespread phenomenon that has been a major driver of low pay.25 Of all hours worked by all Australian women in 2021, 8.1 per cent were worked in aged care, disability support, veterans’ care or ECEC.26 Smart investments in care and support system will support the large numbers of women working in the sectors within it. It will also encourage a move away from a highly gender segregated workforce, thus encouraging more male participation and helping address skill shortages.

This Care and Support Economy Strategy provides an opportunity to properly value care and support work, getting us a step closer to gender equality.

- These are services such as health care, education and social assistance, typically provided free of charge or at prices well below cost, usually funded and regulated by government.Return to footnote 5 ↩

- The ‘health and social assistance’ industry includes health services, ECEC, disability support and aged care. Return to footnote 6 ↩

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics), Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, ABS, February 2023, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 7 ↩

- NSC (National Skills Commission), Employment Projections, NSC, 2021, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 8 ↩

- GVA measures the contribution of an industry to the overall economy. It is a useful economic indicator of economic productivity and performance; PM&C analysis of ABS System of National Accounts data. Return to footnote 9 ↩

- Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women's Voices): Securing our Rights, Securing our Future Report (2020). Australian Human Right Commission. P. 327. Return to footnote 10 ↩

- Walsh & Puszka (2021) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices in disability support services: A collation of systemic reviews, Commissioned Report, Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National UniversityReturn to footnote 11 ↩

- Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women's Voices): Securing our Rights, Securing our Future Report (2020). Australian Human Right Commission. P. 327.Return to footnote 12 ↩

- https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/australian-unpaid-care-work-and-the-labour-market.pdfReturn to footnote 13 ↩

- PM&C analysis; ABS System of National AccountsReturn to footnote 14 ↩

- Treasury (Department of the Treasury), ‘2021 Intergenerational Report: Australia Over the Next 40 Years,’ Treasury, June 2021, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 15 ↩

- Treasury, 2021 Intergenerational Report, [168].Return to footnote 16 ↩

- NSC (National Skills Commission), ‘The State of Australia’s Skills 2021: Now and Into the Future,’ National Skills Commission, 2021, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 17 ↩

- 5-Year Productivity Inquiry: Advancing Prosperity – Volume 1,’ Productivity Commission, 7 February 2023, [19] accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 18 ↩

- NDIA (National Disability Insurance Agency), ‘Active participants by Age Group Q2 FY22/23’, Explore data | NDIS, accessed May 2023.Return to footnote 19 ↩

- PM&C analysis of ABS Participation, Job Search and Mobility survey, 2021 release on Tablebuilder.Return to footnote 20 ↩

- PC (Productivity Commission), ‘Senate Select Committee on Work and Care: Productivity Commission Submission,’ Productivity Commission, September 2022, [5] accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 21 ↩

- WGEA (Workplace Gender Equality Agency), ‘She’s Price(d)less: The Economics of the Gender Pay Gap,’ WGEA, prepared with DCA and KPMG, 13 July 2022, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 22 ↩

- The Senate, Finance and Public Administration References Committee, ‘Gender Segregation in the Workplace and Its Impact on Women’s Economic Equality,’ Parliament House, June 2017, accessed April 2023.Return to footnote 23 ↩

- Data on the veterans’ workforce is not available; PM&C analysis of ABS Census occupational data. Informal carers data from Informal carers - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (aihw.gov.au)Return to footnote 24 ↩

- World Health Organisation, ‘Delivered By Women, Led By Men: A Gender and Equity Analysis Of the Global Health and Social Workforce,’ Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 24, 2019, [3] accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 25 ↩

- PM&C analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing, 2021.Return to footnote 26 ↩