The need for a safe work environment

All workers are entitled to safe and healthy work. It is also critical to preventing physical and psychological harm. Creating and maintaining a safe and healthy workplace is a legal requirement.

The Australian Government is serious about supporting improved work, health and safety outcomes for all workers.

Workers in the care and support economy perform a broad range of roles. For these workers, their workplaces may change day-to-day and many may work alone, increasing risks to their health and safety. Many care and support roles can be physically demanding, emotionally confronting, repetitive, and expose the workers to workplace stress and violence.

Well understood hazards and risks in the care and support economy include manual handling from lifting, supporting and moving people, as well as repetitive tasks, exposure to biological hazards, fatigue and shift work, and slips, trips and falls.

Psychosocial hazards, such as high work demands, low job support, and harmful behaviours also pose risks of physical and psychological harm. On average, work-related psychological injuries have longer recovery times, higher costs, and require more time away from work. Managing the risks associated with psychosocial hazards not only protects workers, it also decreases the disruption associated with staff turnover and absenteeism, and has economy-wide benefits amounting to billions of dollars each year.66

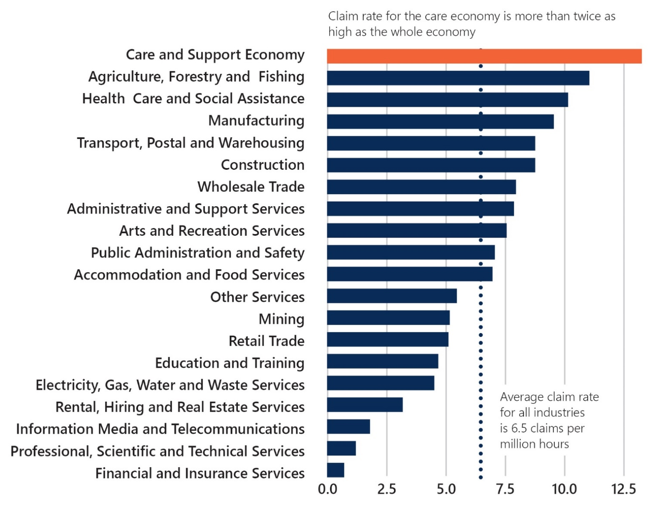

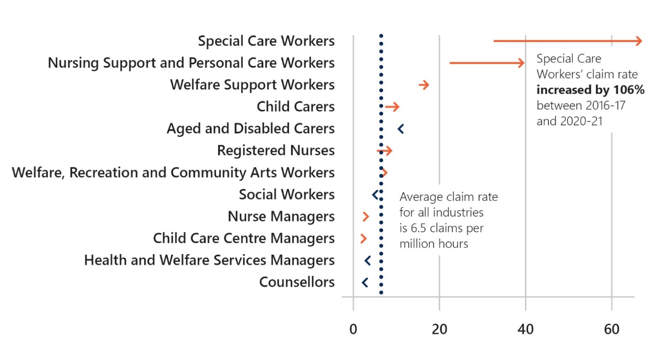

ABS data show that across the whole of Australia in 2021-22, community and personal service workers was the occupation group with the highest rate of work-related injuries.67 Data from Safe Work Australia also show that serious claim frequency rates for the care and support economy were more than twice that of the all-industries average in 2020-21. A high proportion of these were for physical injuries.

Additionally, the rate of injuries in care and support roles has been increasing and is rising at a greater pace relative to other industries. It rose by 25 per cent between 2016-17 and 2020-21.

Research by the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government found 73 per cent of NDIS workers reported their health and safety is at risk at least some of the time.70 The risk to their health and safety was one of the top reasons NDIS workers intended to leave their job.

The need for good job design

High work demand is a psychosocial hazard that can cause harm to workers. Heavy workloads can also be distressing for workers when they believe they do not have the resources they need to deliver quality care and support (termed ‘moral distress’). Administrative burden can contribute to workers feeling they are not doing the work they should be. Many early childhood educators and NDIS workers are overwhelmed by paperwork, which they see as a barrier to quality interactions with children and participants, and a major contributor to unpaid work.71

Heavy work demands are currently widely reported across the care and support economy:

- Most early childhood educators do unpaid overtime regularly72

- 51 per cent of NDIS workers reported weekly unpaid work73

- High workloads are the most common source of job dissatisfaction reported by aged carers

Research into NDIS workforce retention found that cultivating balanced workloads is one of the factors that would drive significant improvements in employee retention. Streamlined paperwork, satisfaction with quality of service delivered, and supportive workplace cultures are others.74 Workloads have also been found as one of the most important factors when considering improvement of ECEC jobs.75

Among NDIS workers, 43 per cent feel burnt out at least some of the time.76 Anywhere between 30 and 50 per cent of aged care workers in direct care and support are affected by burnout.77

Other commonly reported hazards affecting the care and support workforce include low job control, poor support, lack of role clarity, and poor organisational change management. The risks posed by such hazards are likely to be exacerbated by workforce shortages.

These hazards and heavy workloads are elements of the way that work is designed and organised, which could be addressed by improving job design in the care and support economy. Improving good work design would involve considering the way that work is performed, worker needs, preferences and capacities, the physical environment, and systems and processes (including regulatory settings) and how these factors interact.78

Good job design can also help address worker shortages: it can improve employee retention by increasing job satisfaction and improving work health and safety outcomes. It can also drive innovation and productivity improvements.

Racism and sexual harassment of workers

High proportions of workers in the care and support economy are from culturally diverse backgrounds and have reported experiences of racism, both from other workers and from those they are providing care and support to.

Reports of sexual harassment are also unacceptably high, with 33 per cent of workers in Health care and social assistance reporting experiencing sexual harassment.79 This is unacceptable in Australia.

Employers also have a legal requirement to prevent employees being exposed to harmful behaviours. Mitigating these harmful behaviours is necessary as they pose risks to employees and may impact worker retention.

Developing and supporting a diverse workforce also enhances capability in meeting the varied needs of those accessing care. For example, as discussed above, having First Nations care and support workers is very important in First Nations communities. However, available data suggests that overall, the First Nations workforce in the care and support economy is emerging or limited.

Objectives

2.2 Work is organised and jobs are designed in a way that promotes good job quality and worker satisfaction

2.4 Workplaces are safe and healthy, and psychological and physical risks are eliminated or, if this is not possible, minimised

2.5 Improved leadership and management capability across the care and support economy

2.6 Workplaces are inclusive of diverse cultures, genders, ages and abilities and are culturally safe for all workers, including First Nations workers

How will we get there?

Recent updates to Australia's model work health and safety laws have been made to clarify the existing obligation to manage psychosocial risks. An accompanying model Code of Practice on managing psychosocial hazards at work was also published by Safe Work Australia. The majority of jurisdictions have either implemented or are in the process of implementing regulations dealing with psychosocial hazards.

Improving workplace safety for workers in the care and support economy needs to be a priority. The Australian Government will work with state and territory governments, who are constitutionally responsible for workplace health and safety, and other relevant stakeholders on a Worker Safety Action Plan.

The Australian Government will commission expert analysis into the drivers of unsafe work practices and high workloads (and job design more broadly) in the design of programs and regulation. Actions to address issues identified in this analysis will be included in the Pricing and Market Design Action Plan.

- Safe Work Australia (2022), Safer, healthier, wealthier: the economic value of reducing work-related injuries and illnesses, accessed May 2023.Return to footnote 66 ↩

- ABS, ‘Work-Related Injuries,’ ABS, 15 February 2023, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 67 ↩

- Safe Work Australia, data produced for the Care and Support Economy Taskforce, January 2023. Return to footnote 68 ↩

- Safe Work Australia, ‘Analysis of Work-Related Injuries.’Return to footnote 69 ↩

- BETA, ‘NDIS Workforce Retention.’ [23]Return to footnote 70 ↩

- E Harper, et al., The early learning work matters project. Return to footnote 71 ↩

- United Workers Union, 'Exhausted, Undervalued and Leaving: The Crisis in Early Education', VOCED, 2021; E Harper, S McGrath-Champ and R Wilson, The Early Learning Work Matters Project: Findings from Phase II, 2022, Rattler 140: 32-35.Return to footnote 72 ↩

- BETA, NDIS workforce retention.Return to footnote 73 ↩

- BETA, NDIS workforce retention.Return to footnote 74 ↩

- K Thorpe, E Jansen, V Sullivan et al., Identifying predictors of retention and professional wellbeing of the early childhood education workforce in a time of change, Journal of Educational Change, 2020 21: 623-647, doi:10.1007/s10833-020-09382-3.Return to footnote 75 ↩

- BETA, NDIS workforce retention.Return to footnote 76 ↩

- ARIIA (Aged Care Research & Industry Innovation Australia), 'Staff Burnout Rapid Review', n.d., ARIIA, accessed April 2023. Return to footnote 77 ↩

- Safe Work Australia (2020), Principles of Good Work DesignReturn to footnote 78 ↩

- AHRC, Everyone's business: Fourth national survey on sexual harassment in Australian workplaces, AHRC, 2018. More precise data was not obtainable for this Strategy.Return to footnote 79 ↩