When the COVID‑19 pandemic emerged at the start of 2020, governments around the world were ill prepared to respond to the scale and duration of a crisis that had ramifications for our health systems, our economies and the very function of our societies. Australia was no exception, with pre‑existing pandemic plans limited in scope and lacking the resources to keep them up to date.

None of the plans anticipated that, when faced with the prospect of significant loss of life and an overwhelmed health system, leaders would choose the previously unthinkable to protect their citizens. As a result, we had no playbook for pivotal actions taken during the pandemic, no agreement on who would lead on taking these actions and no regular testing of systems and processes. It is telling that there were no plans for the execution of key measures, such as closing our international borders and enforced quarantine. As a result, the pandemic response was not as effective as it could have been.

Despite this lack of planning, Australia fared well relative to other nations that experienced larger losses in human life, health system collapse and more severe economic downturns. Our Inquiry, which focused on the actions of the Australian Government, has concluded that this was due to a combination of factors including early and decisive leadership and the collective efforts of the general public, community organisations, businesses, essential workers and the public service. Above all, Australia’s success in responding to the pandemic was a testament to the willingness to put community interests ahead of self‑interests and to all do our bit as part of ‘Team Australia’.

The pandemic emergency response did not last weeks or months, but for more than two years. It involved community‑wide sacrifices and health, economic and social impacts that continue to be felt almost five years after the pandemic started. Tragically, tens of thousands of Australians were directly impacted by the severe illness and loss of life. And every member of the community was impacted by the significant limits on freedom of movement, disruptions to schooling, reduced access to usual health care, separation from family and friends, or the loss of work and businesses.

While governments were united in their ambition to minimise the harm of the pandemic, there are lessons to be learned for the future. We have lived through the most significant global health emergency in 100 years, and have an opportunity to record what worked and what we would recommend the Australian Government does differently the next time it faces a pandemic.

The Inquiry was also asked by the Australian Government to provide its recommendations, based on what we learned through the COVID‑19 pandemic, on the guiding principles and priorities for the Australian Centre for Disease Control (CDC). The CDC is an important addition to the public health infrastructure in Australia and it is taking early steps to strengthen our preparedness and improve our resilience.

We know that another pandemic could occur at any time, and it is imperative that governments are prepared. We know that the next pandemic may involve a more lethal virus that is harder to contain. We know that a future pandemic is likely to be compounded by concurrent crises which include natural disasters, cybersecurity threats and geopolitical tensions. Next time, we cannot say it was unprecedented. We must act now to apply lessons learnt during the COVID‑19 response to strengthen our national resilience to the next crisis and avoid repeating the same mistakes.

Back to topOur approach

In undertaking its work, the Inquiry consulted widely and leveraged the latest data and evidence on the impact of key decisions taken during the crisis. The Inquiry heard from key decision‑makers in leadership positions at the time, including the former Prime Minister, senior Cabinet ministers, Premiers, Chief Ministers and public servants. These leaders shared insights for their successors in the event of a similar crisis on actions to minimise harm and achieve the best possible health, social and economic outcomes.

The Inquiry received 2,201 public submissions from 305 organisations, 1,829 individuals and 67 anonymous contributors, representing a breadth of experiences and reflections from across governments, businesses, community organisations, unions and everyday Australians.

A total of 27 roundtables with stakeholders involving more than 300 individuals were held to test the Inquiry’s understanding of what worked well and what needs to change. We commissioned a community input survey and lived experience focus groups to ensure the voices of a diverse range of Australians were considered in our review. We thank them for their commitment and trust in voluntarily and openly sharing their views, experiences and advice on how to make our future pandemic responses stronger.

These consultations have informed nine key recommendations aimed at shaping future pandemic responses. To place Australia in the best possible position to detect and respond to the next pandemic, the Inquiry has identified 19 immediate actions (numbered 1 to 19 below) to be undertaken in the next 12 to 18 months and seven medium-term actions (numbered 20 to 26 below) to be implemented ahead of the next pandemic. Organised around nine key pillars of an effective pandemic response, they provide a high‑level playbook for the future.

This summary report evaluates the Australian Government’s COVID‑19 response through each of these pillars and the key lessons learned through Australia’s experience of the pandemic. This report augments the Inquiry’s main report, which provides more detail of the Australian Government’s response, its impacts and the panel’s evaluation, key learnings and actions. Together these reports document what worked well, what did not, what has changed since the pandemic and what still needs to be done to prepare for the next crisis.

Back to topCOVID-19 in Australia

The story of COVID‑19 in Australia is not a static one. As new waves and virus variants emerged, infection and transmission risks shifted, and government responses and community attitudes and behaviours changed.

For most Australians, their understanding of the pandemic was marked by their experiences: the time they spent away from loved ones, changes to work or study, health or financial challenges and personal tragedies. We are conscious that many Australians continue to be affected by the tail of the pandemic. Their experiences include fear of ongoing infection risk; health impacts from infection, vaccination or disruption to health care access; mental health impacts; and ongoing employment and financial impacts.

However, for ease of reference this report divides the period between the arrival of COVID‑19 in January 2020 and today into four ‘phases’: alert, suppression, vaccine rollout and transition/recovery.

Back to topThe alert phase: January to April 2020

Human-to-human transmission of SARS‑CoV‑2, the virus that causes COVID‑19, was confirmed by health experts in China on 20 January 2020.1 The first case of COVID‑19 in Australia was detected just days later, on 25 January 2020.

Over the next two months, Australia began to activate its emergency settings in response to the threat posed by the virus. COVID‑19 was added as a disease ‘with pandemic potential’ to the relevant determination under the Act by the Chief Medical Officer in January 2020. It was a critical moment when, on the advice of the Minister for Health, the Governor‑General declared a ‘human biosecurity emergency’ under section 475 of the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Cth) (the Biosecurity Act) on 18 March 2020.

When the human biosecurity emergency was declared, the Minister for Health had the capacity to access extensive powers under the Biosecurity Act to determine measures to prevent or control the entry or spread of COVID‑19 in Australia. This was the first time that these powers under the Act had been used since its enactment.

On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID‑19 to be a pandemic and by 22 March 2020, 1,765 confirmed cases, including seven deaths, had been reported in Australia.

Australia’s crisis response rapidly escalated. All governments followed a ‘precautionary’ approach to slow the spread of COVID‑19 in the community, protecting at-risk populations and preparing the health system. Governments restricted travel into and around Australia and introduced wide‑ranging public health orders. Things came to a head when the first national lockdown was implemented on 29 March 2020.

A series of economic packages in March represented the biggest ever fiscal expansion in Australia’s history, totalling $213.7 billion. The biggest program, a wage subsidy scheme called JobKeeper, ended up supporting almost a third of jobs across the economy.2

Throughout this period, the country’s most senior leaders met regularly through National Cabinet, which was established to address the pandemic and replaced less agile Commonwealth–state forums. Policy responses initially focused on the short‑term public health implications, but quickly widened as the pandemic transformed into an economic and whole‑of‑society crisis.

For Australians, this period was marked by significant changes to their lives, uncertainty about the virus, and fear based on devastating images of COVID‑19 experiences overseas. Globally, there was uncertainty about whether a vaccine or treatment for COVID‑19 would be developed.

Back to topThe suppression phase: May 2020 to January 2021

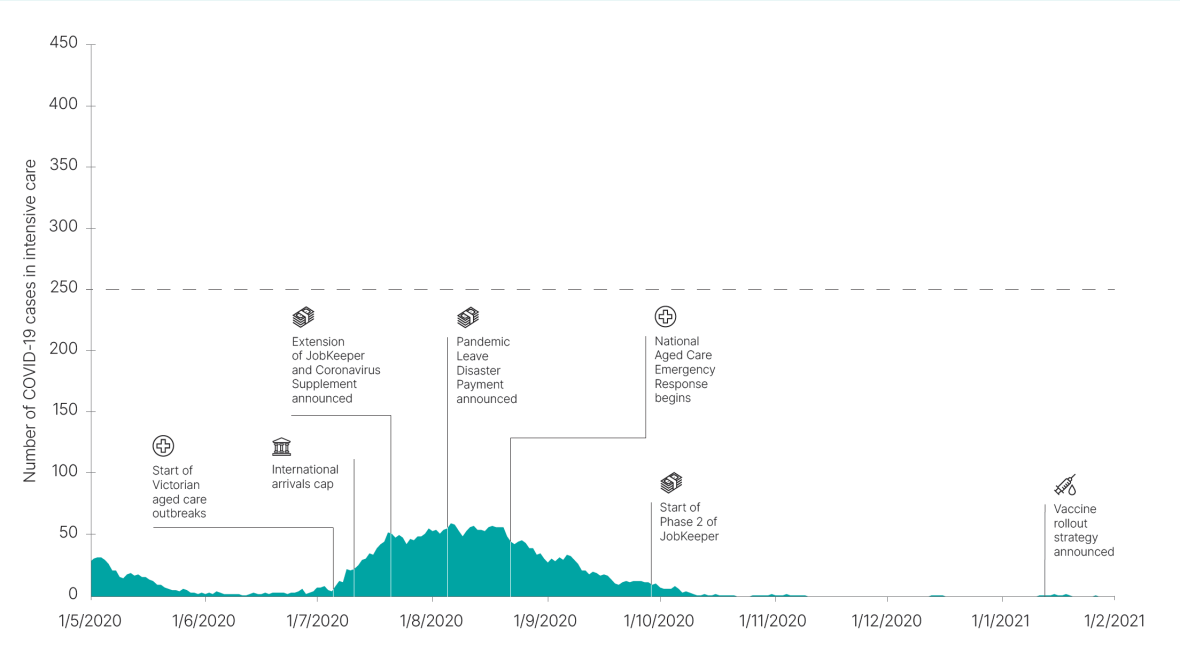

Text description of Figure 1

Timeline of key pandemic events from May 2020 to February 2021 mapped against the number of COVID-19 cases in ICU.

COVID-19 cases in ICU were 27 on 1 May 2020 and decline to 1 June 2020.

COVID-19 cases in ICU rise again from 1 July 2020 to peak at 49 by 20 July 2020 before declining again from the middle of August 2020.

Key events identified are:

- Start of Victorian aged Care outbreaks 8 July

- International arrivals cap 10 July 2020

- Extension of JobKeeper and Coronavirus Supplement announced 21 July 2020

- Pandemic Leave Disaster Payment announced 3 August 2020

- National Aged Care Emergency Response begins 21 August 2020

- Start of Phase 2 of JobKeeper 28 September 2020

- Vaccine rollout strategy announced 7 January 2021.

Australia moved into an extended period of striving to curtail transmission and keeping case numbers low to ensure that optimal care (especially in intensive care units) would be available to all COVID‑19 cases, and minimising impacts on the access to usual healthcare for the general population.

This phase saw government responses begin to diverge as some areas maintained low case numbers and largely returned to life as normal, whilst others experienced high case numbers and imposed lengthy lockdowns.

By late 2020 it had become clear that the pandemic would not be short‑lived. Australians adapted work and study approaches where they could, and many experienced significant challenges juggling the demands of work and caring responsibilities. Essential workers in health, aged care, disability and early childhood education and care were particularly stretched and expressed concerns about the risks to their physical and mental health.

The significant burden beyond the health system became apparent during this period. In particular, many people were negatively affected by lockdowns and the closure of businesses that had implications for their financial security. The Australian Government continued to provide the financial supports that had been introduced in the alert phase and introduced a range of packages for specific sectors that had experienced ongoing disruption or had not benefited from earlier supports.

Meanwhile, experts around the world continued to work to develop vaccines, with trials focused on the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing the severity of illness and death. Countries took different approaches to secure vaccine supply, and Australia found itself struggling against more proactive efforts from other governments, perceptions of greater need given the success of our suppression strategies, and the lack of domestic manufacturing capability.

Back to topThe vaccine rollout phase: February to November 2021

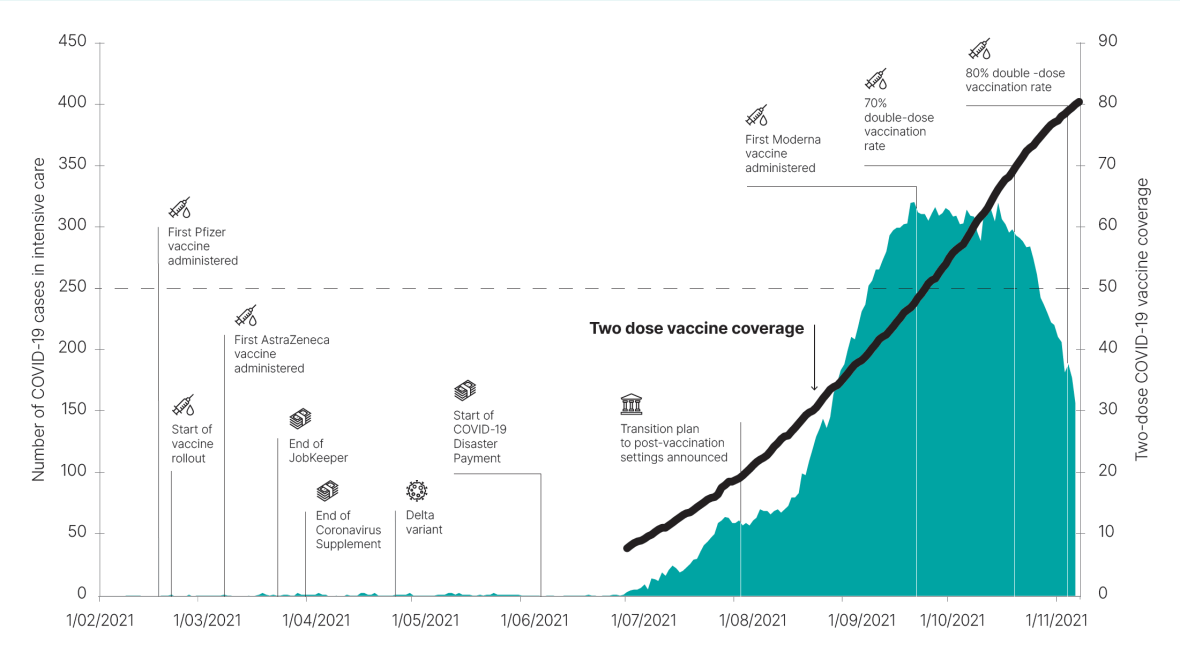

Text description of Figure 2

Timeline of key pandemic events from February to November 2021 mapped against the number of COVID-19 cases in ICU and two-dose vaccine coverage.

This shows a big rise in cases from July 2021 that begins to decline when 70% double dose vaccination coverage is reached.

Key events identified are:

- First Pfizer vaccine administered 21 February 2021

- Start of vaccine rollout 22 February 2021

- First AstraZeneca vaccine administered 7 March 2021

- End of JobKeeper 28 March 2021

- End of Coronavirus Supplement 31 March 2021

- Delta variant 27 April 2021

- Start of COVID-19 Disaster Payment 19 June 2021

- Transition plan to post-vaccination settings announced 6 August 2021

- First Moderna vaccine administered 22 September 2021

- 70% double-dose vaccination rate 20 October 2021

- 80% double-dose vaccination rate 6 November 2021

Australia’s vaccine rollout commenced on 21 February 2021, using a phased approach that prioritised groups considered most at risk of exposure to the virus or of experiencing severe illness or death.

As Australia had been slower than some countries to approve the use of vaccines and secure supply, it continued to rely on suppression strategies and ongoing international border restrictions to manage the virus in the community. The main consideration was reaching an adult vaccination rate where enough Australians were protected from severe disease for the health system to cope alongside providing critical health services for non‑COVID related medical conditions.

The delays in vaccine procurement and distribution, further complicated by concerns over serious side effects, ultimately affected the duration of the vaccine rollout and prolonged restrictive public health measures. The additional lockdowns that occurred as a result of these delays had a direct economic cost estimated at $31 billion.5

From the middle of this phase, the Delta variant spread through communities in the eastern states, triggering extended lockdowns in some jurisdictions. The spread of the virus also extended to areas that had previously remained free of COVID‑19, including some remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Discussion regarding the path to easing restrictions began with agreement at National Cabinet and the release of the National Plan to Transition Australia’s National COVID‑19 Response on 9 July 2021. The plan set out a four-step transition to shift the focus from suppressing viral spread to preventing as much severe illness and death as possible as the virus became endemic in Australia. However, the plan had to be updated soon after its release to account for the arrival of the Delta variant and its increased transmission potential and disease severity. The amended plan was published on 6 August 2021. A key change was the increase in the adult vaccination target from 70 to 80 per cent, which was reached in November 2021.

Vaccine mandates for health and aged care workers had been put in place, and these were extended by jurisdictions and employers to include a range of frontline workers and others, including construction workers in some jurisdictions. Governments also required people to be fully vaccinated to participate in some social and work‑related activities. Those who were not fully vaccinated during this period were often still subject to restrictions.

Whilst vaccine effectiveness against infection waned after a few months, and more rapidly with the Delta variant, vaccines continued to protect people from severe disease and death, as well as being protective against long COVID.

Throughout this period, many Australians felt uncertain about when they would be able to return to normal life, while others were fearful about the lifting of restrictions. Those who lost employment or were unable to participate in some activities due to their vaccine status became increasingly distrustful of public health orders and angry about their treatment.

Back to topThe transition/recovery phase: December 2021 to the present day

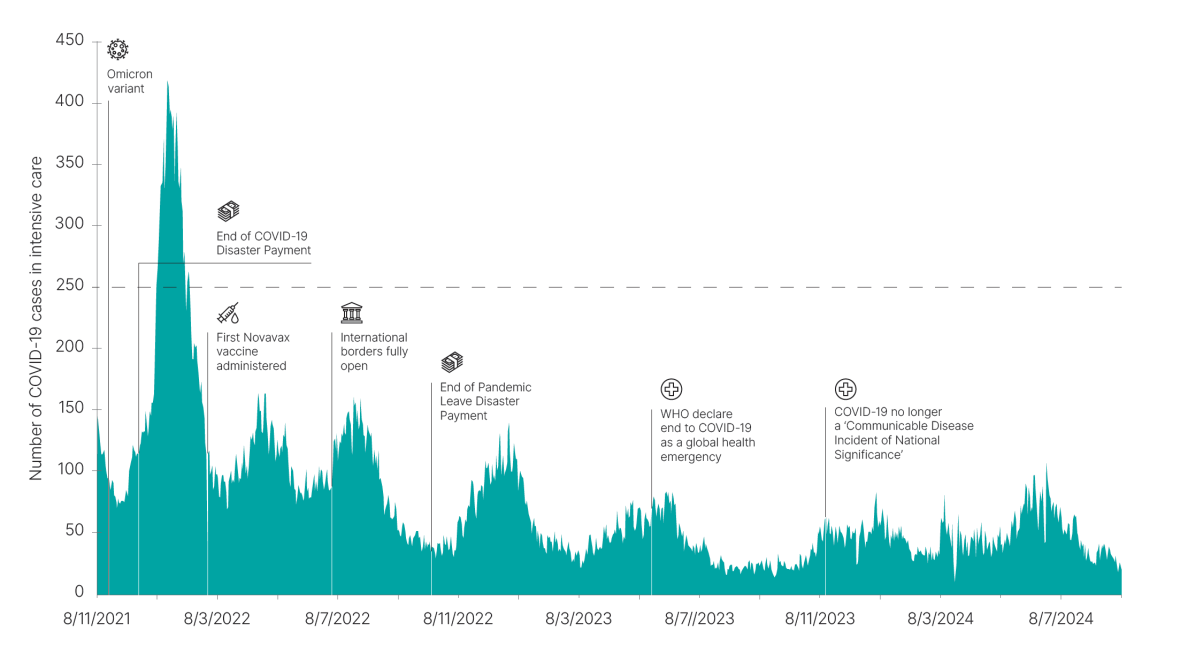

Text description of Figure 3

Timeline of key pandemic events from November 2021 to September 2024 mapped against the number of COVID-19 cases in ICU.

The number if COVID-19 cases in ICU rises quickly to a peak of 419 in January 2022, before declining quickly.

Key events identified are:

- Omicron variant 24 November 2021

- end of COVID-19 Disaster Payment 20 December 2021

- First Novavax vaccine administered 15 February 2022

- International borders fully open 6 July 2022

- End of Pandemic Leave Disaster Payment 30 September 2022

- World Health Organization declare end of COVID-19 as a global health emergency 5 May 2023

- COVID-19 no longer a Communicable Disease incident of National Significance 20 October 2023

Once vaccination targets were reached, the Australian Government announced that Australia could ‘transition to living with COVID‑19’. During this period, there was a reopening of state and international borders, an easing of restrictions and a strong economic recovery. As some looked to move on from the pandemic, there was a rapid de-escalation in COVID‑19 communications. This caused many to feel uncertain as they had become accustomed to regular reporting of infection and vaccination statistics. The concept of ‘living with the virus’ was also polarising, with some arguing we should have done this all along, whilst others felt this was downplaying the importance of COVID‑19, and implied tha it was the same as a cold or the flu.

The arrival of the more transmissible Omicron variant coincided with this period of opening up and consequently Australia experienced its first true community‑wide exposure and infection. Omicron’s arrival also made clear that containment measures could no longer work in the same way, and Australia had no choice but to consider COVID‑19 an endemic disease and plan accordingly.

During this time, many Australians returned to a life not too dissimilar from the one they knew before the pandemic. However, some people felt unsafe as restrictions eased and others continue to grapple with the ‘long tail’ of physical and mental health impacts of the virus and the government response.

The pandemic has also had other consequences. There are much higher levels of vaccine hesitancy, a decline in COVID‑19 booster uptake, and lower general vaccination uptake, including among priority populations and people over 75, who are generally more at risk of severe disease.

The Human Biosecurity Emergency Declaration under the Biosecurity Act lapsed on 11 April 2022, signalling the beginning of the end of the pandemic emergency response. On 20 October 2023, Australia declared that COVID‑19 was no longer a Communicable Disease Incident of National Significance.

SARS‑CoV‑2 variants continue to circulate in our community today, and COVID‑19 is monitored and managed as one of Australia’s notifiable communicable diseases.