Feedback received from the community suggests that improving the performance of public service delivery through the use of AI offers a significant opportunity to build agency trustworthiness

The performance of public services – how well the system meets user’s expectations – is a critical attribute of a trustworthy agency. Survey respondents reported that meeting users’ needs and delivering efficient, timely, good quality and reliable services, is important for them to trust public services.[29] To respondents, trust meant:

…a reputation for quality, timely service delivery, engaging with empathy and following through on what [they] say [they] will do. Public services need to be reliable, consistent, contemporary and meet the needs of all Australians.

The capacity of government to commit to and deliver high-quality public services that are sustainable and provide inclusive and genuine benefits.

The community expressed a higher degree of trust in government’s ability to use AI to improve some aspects of the performance of public services than others. For example, 42% of survey respondents indicated that they trust government’s ability to use AI to deliver services faster. However, trust was lower in government’s ability to provide personalised services. Similarly, community representatives indicated that they saw opportunities for governments to use AI to provide information faster in transaction type services, where people want to get what they want without needing to talk to a human. Community representatives also saw opportunities to simplify bureaucratic processes, optimise resource allocations, and reduce wait times by leveraging AI as a ‘sidekick’ for public servants.

AI systems need to be well-designed to improve public service performance

There was a strong view that public service design mattered – for AI-enabled public services and the APS as a whole:

[Trust in the context of public services means]…”That the services provided have been well designed with the end users’ needs in mind

Many community representatives argued that managing the risks and benefits of AI in public services can only realistically be achieved with design input from those who use those services. To achieve the potential benefits of AI-enabled service delivery, community representatives suggested that the developers of AI algorithms and systems would require a detailed understanding of lived experiences of the broader community, and the experience of specific groups, for example cohorts who experience vulnerability, that rely on service delivery in particular. Equally, community representatives recognised the risk of harms arising from the lack of diverse perspectives in AI design processes, noting that this could lead to unintentional biases and stereotypes being perpetuated.

Implementing AI in public service delivery well – in ways that demonstrate and build trustworthiness – critically depends on establishing and acting with integrity

In the APS, integrity means:

…doing the right thing – both in ‘what’ we do and in ‘how’ we do it. Integrity is about demonstrating sound ethics and values through our work and our behaviour, and earning trust in our ability to act in the best interest of the Australian community.[30]

Simply put, acting with integrity means adhering to a set of principles that the community finds acceptable, in terms of both words and actions.

The ANU Rapid Evidence Assessment of the literature suggests that there is significant overlap between factors that are important for the integrity of the public service and factors that ensure that AI systems are designed, developed and implemented with integrity:

- Ethics and values: AI systems should be designed and developed with ethical principles in mind, including the principle of to do no harm. In the context of public service delivery, this means mitigating the risks of bias and discrimination through managing data collection, storage, pre-processing, and algorithm design to ensure fairness in outcomes.

- Accountability: The people and organisations employing AI should be accountable for the outcomes and decisions of AI systems. In the context of public service delivery, this means understanding who is responsible for the AI’s behaviour (developer, agency etc.), and having avenues for appealing outcomes.

- Transparency: Transparency in AI refers to the openness and comprehensibility of the AI systems’ operations and decision-making processes. Transparency aids in accountability. In the context of public service delivery, services that involve AI should provide understandable, audience-appropriate explanations of decision-making processes and outcomes. Given that end users will have varying knowledge of AI – as outlined above, more than half of Australians (57%) report having zero or slight knowledge of AI – this means conveying an effective mental model of the AI system’s decision process to an end user, even if they don’t fully understand the internal workings. This may involve simplifying the true decision process to capture the most relevant factors and derive generalisable insights.[31]

Acting with integrity takes on a particular importance in the case of the APS’ adoption and use of AI (Box 4). In part, this reflects some properties of AI and the need to address associated risks and concerns. Many types of AI are black box technologies – for example, generative AI like ChatGPT built on large language models and multimodal foundation models – making it difficult or even impossible for most people to understand how the model arrived at its outputs.[32] Addressing the risks involved in the use of generative AI tools in a government context, including the risks of erroneous, misleading or inappropriate outputs in response to prompts, means being clear when those AI tools are being used by government to inform activities. It also means ensuring that the bounds on the role of AI tools in decisions and outcomes – for example, that generative AI tools are not the final decision-maker on government services – are clearly communicated.[33]

Box 4: Integrity is important in the context of AI

Like all technologies, AI can be used for positive or harmful purposes.[34] However, the nature of AI models, combined with their capacity to learn from vast and diverse datasets, can make predicting their behaviour challenging.

- AI is unique because of the scope of what is possible. It can take actions at a speed and scale that would otherwise be impossible (with implications for both benefits and harms).[35]

- There may be potentially unforeseen patterns in the data that make it hard to know precisely how AI will generate its decisions and outputs. The extent of this risk significantly depends on the model used, and its training data. Different models have different complexities, and if the training data is incomplete, biased or unrepresentative, the AI’s behaviour can reflect those shortcomings, making it challenging to predict how it will behave in various situations.

- It is impossible to guarantee that the AI knows, and has learned, what was originally intended by the developer. The challenge of certifiability in AI lies in developing consistent and widely accepted criteria to assess and ensure the reliability, safety and ethical compliance of AI systems across various use cases. Given the diversity of AI models, applications, and data sources, creating a unified framework for certifying AI’s performance and behaviour becomes complex, requiring careful consideration of technical, ethical and societal factors.

However, there is a range of tools that agencies can use to address these risks from a technical and/or procedural angle, to help agencies to develop, use and implement AI systems in trustworthy ways. This includes Australia’s AI Ethics Principles;[36] the OECD Principles on AI and its associated guidance on tools for implementing trustworthy AI systems[37]; the Commonwealth Ombudsman's Automated Decision-Making Better Practice Guide[38] and the DTA guidance on public sector adoption of AI as part of its Australian Government Architecture, including the Interim guidance for agencies on government use of generative Artificial Intelligence platforms.[39] Agencies also have in-house tools and guidance, such as the ATO data ethics principles.[40]

Integrity was by far the most important dimension of trustworthiness for participants of workshops held with AI and APS experts and the community. Community representatives highlighted that AI systems and tools themselves need to be implemented in ways that demonstrate accountability, transparency and adherence to ethical values, in other words, with integrity.

I trust public service delivery when final decisions are transparent and adequately explained. AI can feel like a black box for people, it’s not clear how it actually came to the conclusion.

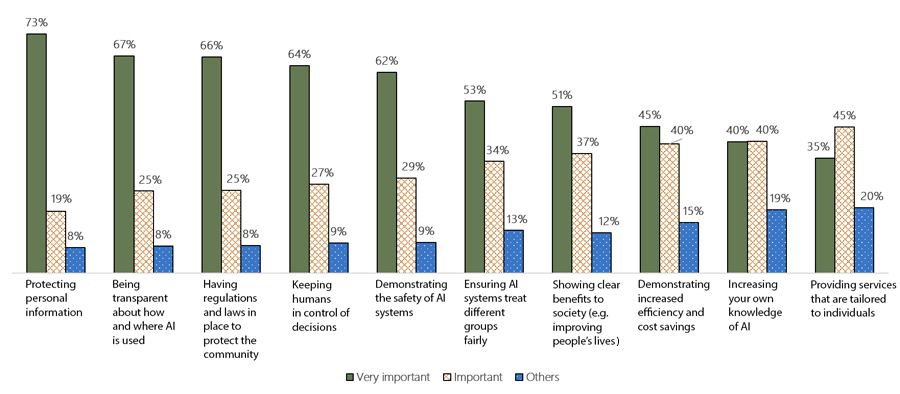

For example, there was a view that the increased scale and speed of an AI-enabled system would require increased oversight to ensure the integrity of the system, the integrity of the data, and the value to the public of the outcomes. Similarly, the Survey of Trust in Australian Democracy found that three in four Australians consider protecting personal information as very important; and around 2 in 3 consider that transparency in how/when AI is used and laws/regulations protecting community is also very important (Figure 10)

Trust in the public service means that there is integrity within the services delivered. That people in the public service are acting with integrity to create and deliver services that improve all Australians and do not embed biases.

Acting and making decisions in the best interest of the Australian public. Being able to believe that decisions made are considered and are made in good faith.

Notes: Results show importance given to each of the listed factors in trusting government agencies to use AI. Others include results for people who selected “Somewhat important”, “Not important at all” and “Not sure”.

Source: Australian Public Service Commission, Survey of Trust in Australian Democracy (forthcoming)

Personal privacy and data security are very important for the community

AI-enabled public services will rely heavily on data from the community, yet for many in Australia, use of personal data by AI is a significant concern. For example, a recent report by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) finds that 43% of people in Australia say that AI using their personal information (in both businesses and government agencies) is one of the biggest privacy risks they face.[41]

For many workshop participants and survey respondents, the trustworthiness of a system that used personal data centred on knowing when data was being collected, knowing how data was going to be used, and being able to opt out of collection at any time (Future scenario 1). Participants emphasised that the trustworthiness of a system (or agency) would be drastically reduced if it could not guarantee that their personal data would not be shared with private organisations, or that it would be stored outside of Australia’s borders. There was also some concern that there was no way to guarantee the integrity of future governments and how they may use people’s personal information.

Future scenario 1: High personalisation and intervention

This scenario asked workshop participants to consider a future where AI integration with public services was entirely co-designed with community. In this scenario, a comprehensively co-designed model incurred a delay in implementation, but allowed for services to be delivered through tiered options. The top-tier required extensive collection of personal data and provided a highly-personalised level, which included the option for automated intervention around health, finances and service offerings delivered through a single online platform. The baseline tier provided a greater level of personal privacy and agency, but it came without personalisation and a lower suite of service offerings, some of which could only be accessed via physical shopfronts in major cities. This scenario sought to:

- Understand better the desire within community for a co-designed system of AI-enabled public service delivery, and a willingness to invest in such a process, provoking discussion around potential levels of community engagement and ongoing participation in processes of oversight and integrity assurance.

- Have participants describe their level of willingness to provide high levels of personal data for higher levels of personalisation of service delivery within an AI-enabled system.

- Harvest participant responses around the concept of differing levels of public service delivery, which is based on the amount of data individuals choose to share.

- Have participants consider the possible permanency of data in an AI model once it has been provided, to provoke discussion around the potential for discrimination based on levels of privacy, geographic location and desire for human-in-the-loop service delivery.

We learnt that:

- How comfortable people are with sharing their data with government fundamentally depends on their individual circumstances.

- A highly personalised, fully integrated public service may bring benefits in certain situations, such as only having to tell your story to the government once. But, it may also come with risks in that a single point of access for services also becomes a single point of failure.

- People value the ability to be forgotten, the ability to correct data, and the ability to take context into account in decisions.

- A sensitivity to creating unique experiences and a loss of a shared understanding and awareness of what public services are and how they engage with and support the Australian public.

There were also concerns about sharing of biometric data for identification purposes. For some, this was due to the risk that their identifying data might be used to impersonate them if breached or faked by AI applications. However, a majority of participants were concerned that it would be used to predict their behaviour. This finding reflects OAIC survey results, which indicates that the majority of Australians are not comfortable with biometric analysis, such as using AI to make assumptions or predictions about the characteristics of an individual from their biometric data.[42]

Data sovereignty is a priority for First Nations peoples

Participants in workshops highlighted the data concerns of First Nations people. They noted that many First Nations people are sensitive to the inherent right to self-determination and governance over their peoples, country (including lands, water and sky) and resources. There is a strong desire that data be used in a way that supports and enhances the overall wellbeing of Indigenous people. In practice, this may mean that Indigenous people need to be the decision-makers around how data about them is used or deployed, to build trustworthiness in AI systems and tools within the public sector (Box 5).

Box 5: Indigenous Data Sovereignty

Indigenous Data Sovereignty emphasises the rights of Indigenous communities to control, manage, and benefit from their own data. It acknowledges the historical marginalisation of Indigenous people and their data, and strives to empower these communities to make informed decisions about how their data is collected, used and shared. When Indigenous communities have ownership over their data and are able to co-design custom AI applications, it may help to foster a sense of respect and collaboration, ensuring that AI respects cultural sensitivities, local knowledge and community values. This approach ultimately enhances the credibility and ethical standing of AI systems, promoting a more inclusive and equitable adoption of AI in the public sector.[43]

Insight 1.1: Artificial intelligence regulation and frameworks will build trustworthiness if they are clearly communicated and explained to the community

In practice, the perceived as well as actual integrity of AI systems is important for trustworthiness. Participants in workshops described an expectation that there will be regulations and frameworks in place that ensure fair, accountable and transparent use of AI. Almost a quarter of respondents to the Have Your Say survey suggested that AI use be limited until guardrails like governance and ethics frameworks are established, risks are properly understood, and mitigation strategies and controls are in place.

No public services until governance frameworks are established. Then no service or decision affecting an individual, no law enforcement, until frameworks are proven effective through use in low risk settings.

In fact, there are a large number of current Australian Government initiatives that are relevant to the development, application or deployment of AI (including frameworks that are specific to the public sector) although most take the form of self-regulation and voluntary standards approaches[44] Work is also ongoing to identify potential gaps in the existing domestic governance landscape and whether additional AI governance mechanisms are required to support the safe and responsible development and adoption of AI.[45]

But those frameworks will only build trustworthiness if they are clearly communicated and explained to the community. There was not a strong awareness of initiatives, voluntary or otherwise, let alone understanding of how they work in practice and the protections provided. Similarly, there was low awareness of the roles and responsibilities of different regulators (both sector-specific and economy-wide). Accessible communication will be key, particularly in a crowded and contested regulatory space.