This report provides research evidence to inform the government’s proposed changes to the federal government's paid parental leave (PPL) scheme in 2023–2026. Our report is titled Next Steps in recognition of the proposed changes:

- From 1 July 2023, 20 weeks in total per couple will be available, with 2 weeks reserved each for the mother and father/partner, and 20 weeks in total for a single parent.

- From 2024, 2 additional weeks per year, up to 2026 when 26 weeks in total will be available.

The research evidence and policy design principles we outline also inform these later changes.

With the extension of paid parental leave by 6 weeks from 20 weeks to 26 weeks, announced by the Labor Government as part of the October 2022-23 Budget, Australia has an opportunity to improve the national system according to ‘best practice’ and informed by significant international research evidence and some Australian evidence. There is an opportunity to enable women to participate in the labour market more fully, to develop and embed incentives for fathers to share the care of a baby and to provide flexibility to parents in their use of parental leave. This would reflect the best international evidence on parental policy design for gender equality, the division of unpaid household labour and women’s economic opportunities and security over the life course. It would also reflect the best practice to ensure the wellbeing of mothers, babies and fathers/partners.

The focus of the report, as requested by the Womens Economic Equality Taskforce, is research evidence on:

- reserved leave for fathers

- flexibility of leave use

- concurrency and sharing of leave taking

- bonus leaves.

A number of other issues directly related to the design of best practice paid parental leave are also highlighted for further consideration.

The positive impacts of paid parental leave align with many of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) making the extension of Australia’s paid parental leave system a positive contribution to national efforts to support the SDGs relevant to women and children’s health and wellbeing (Heymann et al., 2017), particularly SDG 1 on poverty alleviation; SDG 3 on good health and wellbeing; SDG 5 on gender equality; SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth; and SDG 10 on reduced inequalities (see Box A).

Box A. Paid parental leave, child wellbeing, economic inclusion and prosperity

“Early experiences have a profound impact on children’s development. They affect learning, health, behaviour and– ultimately – adult social relationships, wellbeing and earnings. Investing in this period is one of the most efficient and effective ways to help eliminate extreme poverty and inequality, boost shared prosperity, and create the human capital needed for economies to diversify and grow.” (WHO, 2018, p. 3)

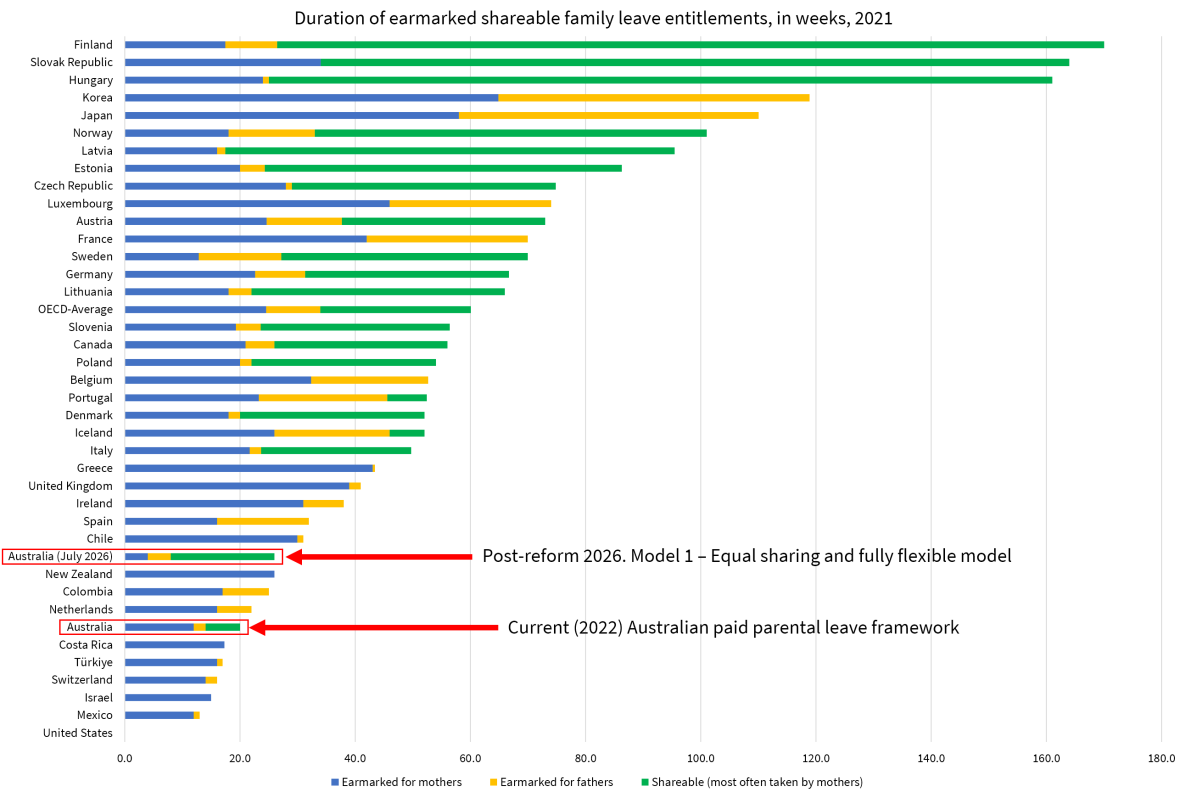

Even with the government’s welcome extension of the national system from 20 to 26 weeks, Australia’s paid parental leave scheme will remain amongst the least generous schemes internationally (OECD, 2022; see Figure 1).

Figure1. International comparison of paid parental leave

We note that there is little systematic data on the decisions made by parents in the use of paid parental leave in Australia to guide policy design and recommend investment in both quantitative and qualitative data collection to inform the roll out of the additional 6 weeks of paid parental leave by 2026. This data will support policy design to best meet the care needs, expectations and aspirations of households. Further research would include evaluation of the Australian experience of paid parental leave use, how households combine the national scheme with employer schemes, interactions between the two schemes, and household preferences for shared care of babies and very young children.

Australia’s Paid Parental Leave Act 2010 provided for a thorough academic evaluation of the policy (see Martin et al., 2014) including its impact on mothers’ and babies’ health, mothers’ workforce participation, and fathers’ and employers’ reactions. Ongoing evaluation of a policy of this type is best practice. Internationally, parental leave schemes are under frequent review and modification as they attempt to meet the needs of contemporary families, economies and international conventions (see Box B). Most recently, some members of the European Union (Denmark and Finland) have revised their paid parental leave policies in response to the current EU Directive.

Box B. International Standards

EU Directive on work–life balance: Implementation 2 August 2022.[1]The Directive on work-life balance aims to both increase (i) the participation of women in the labourmarket and (ii)the take-up of family-related leave and flexible working arrangements. The EU Directive includes:

- Paternity leave: Working fathers are entitled to at least 10 working days of paternity leave around the time of birth of the child. Paternity leave must be compensated at least at the level of sick pay.

- Parental leave: Each parent is entitled to at least four months of parental leave, of which two months is paid and non-transferable. Parents can request to take their leave in a flexible form, either full-time, part-time, or in segments.

International Labour Organization (ILO) Maternity Protection Recommendation, 2000,No. 191.[2]

- Members should endeavour to extend the period of maternity leave referred to in Article 4 of the Convention to at least 18 weeks.

- Provision should be made for an extension of the maternity leave in the event of multiple births.

The Fifty-fourth World Health Assembly, May 2001 Resolution, WHA54.2, on Infant and young child nutrition, paragraph 3(6).[3]

- exclusive breastfeeding for six months as a global public health recommendation.

[1] Directive (EU) 2019/1158 of the European Parliament and of the council of 20 June 2019 on work–life balance for parents and carers.

[2] R191 - Maternity Protection Recommendation, 2000 (No. 191)

[3] World Health Assembly, 54. (2001). Fifty-fourth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 14–22 May 2001: resolutions and decisions. World Health Organization.