Assess demand and calculate the cost

To build a firm foundation for expanding Australia’s approach to prevention, governments must provide adequate funding for DFSV services. For decades, however, services have been chronically underfunded. As reporting rates have steadily increased, this underfunding has created systemic problems that hinder the ability of these services to provide their life-saving services. Faced with critical staffing shortages, many report having no choice but to turn some victim-survivors away; leave phone calls unanswered; and conduct brief risk assessments on lethality to determine who they will be able to assist.

The Review heard about sector-wide frustration, not only in relation to limited capacity to respond to immediate needs, but also missed prevention opportunities to intervene early with families and provide post-crisis support to stop escalating violence, re-victimisation and – in the most severe cases – fatalities. By inadequately funding frontline services, we are undermining a life-saving prevention opportunity.

The Review has also heard there are significant service gaps for diverse and marginalised communities. This includes, but is not limited to: the absence of refuges for LGBTIQA+ people who are excluded from or feel unsafe accessing refuges designed for heterosexual women; limited or no available services for people in remote communities, as well as for adolescents and young people not in the care of a protective parent or who are over a certain age; poor accessibility for people with mobility needs; and people being excluded from existing services as a result of substance misuse, acute mental ill-health concerns or other support needs which sees them labelled as ‘too complex’.

As the Review heard, however, requests for increased funding have only short-term value. Instead, the Review recognises that, before placing a dollar figure on how much is enough, we need to establish national data on current and future demand, and link that to the funding required for services to meet it.

As such, the Review is calling on state and territory governments, and the Commonwealth, to expedite analysis of unmet demand. Based on these findings, all governments should develop sustained funding pathways to meet need. This analysis and response should explicitly address the diverse services need of different groups of people experiencing violence – including First Nations women and communities, LGBTIQA+ people, older women, migrant and refugee women, children and adolescents (including those who are not in the care of a protective parent), women with disability and people with additional support needs (including substance misuse, acute mental ill-health concerns and behavioural needs).

NLAP Findings

The recent Independent Review of the National Legal Assistance Partnership (NLAP) 2022 – 2025 identified that there has been palpable “neglect” of Australia’s legal assistance sector over the past decade. Women’s Legal Services Australia’s submission to this independent view of the NLAP noted that “1,018 attempts to receive assistance were turned away during a 5-day period, which means we [Women’s Legal Services] can estimate that more than 52,000 will be turned away by Women’s Legal Services per year … many of whom are experiencing domestic, family, and sexual violence”.132

More immediately, the Review also recognises that the provision of legal assistance to victim-survivors of DFSV is not only an access to justice issue, but a frontline service that can improve safety and reduce risk. Independent legal advice from publicly funded duty lawyers can help to improve and tailor conditions on protection orders and mitigate against the negotiation of dangerous parenting agreements. Legal advice is also an essential protective element for First Nations mothers whose children are the subject of child protection intervention.133 Further, specialist duty lawyers can ensure that respondents are more likely to understand and comply with these orders, increasing the potential for compliance and de-escalating risk. They also play a pivotal role explaining proceedings, especially when orders are brought by police.

More broadly, access to public legal assistance can function as a protective ‘issues-spotting’ mechanism, whereby wider unmet legal needs – including those that have resulted from or developed in association with the experience of DFSV - can be identified and addressed. This is an area which evidence shows is in much greater need of recognition and which can function as a vital prevention mechanism.134

Urgently, public legal assistance for adult and child victim-survivors in the family law context can mitigate against systems abuse, particularly where practitioners who are adequately trained and trauma-informed should help to give voice to children and young people about their experiences and preferred care arrangements, including in protracted proceedings where the protective parent may be being perceived by the court or portrayed by a perpetrator parent as untruthful. Currently, a persistent lack of funding means that fewer and fewer victim-survivors have access to support, including through legal aid grants which can resource private practitioners.135 Investment in public legal assistance that is directed towards DFSV is therefore a clear mechanism for preventing future – and often irreparable – harm, including harm escalating to homicide. It must therefore be an area of urgent attention.

"The scariest thing about leaving or preparing to leave is not having somewhere to go. Homelessness services are underfunded … so people are faced with either returning to unsafe situations or sleeping rough either by themselves or with children."

– Kelly, victim-survivor.136

High-cost emergency accommodation

The Panel were unable to identify any published and consistent data, either national or at a jurisdictional level, setting out how much money is being spent on high-cost motel accommodation for people experiencing DSFV. However, one state/territory-wide service (who wished to remain anonymous) informed the Panel they are spending approximately $120,000 - $150,000 per month on temporary accommodations to support women and children escaping immediate threats of violence.

Another service provided data to the Review indicating that, between July 2023 and August 2024, they spent approximately $32,000 on motel accommodation for 28 clients for 182 nights.

Noting Australia’s current housing crisis, the Review also recommends immediate action to facilitate crisis accommodation to ensure safety and prevent violence from continuing. This includes the urgent need for trauma-informed crisis accommodation that supports recovery and healing, rather than a “motel model”, which entrenches instability and harm. The Review suggests the Commonwealth Government consider expansion of the Safe Places Emergency Accommodation program, a capital works program funding the building, renovation or purchase of emergency accommodation for women and children experiencing DFSV. All governments should also consider increasing specialist DFSV housing options via the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement. The Review notes that investment in capital works must be considered alongside the required operational funding for services to run.

Further, the Review recognises the need for access to services in some of Australia’s most remote and underserviced communities, including the Torres Strait region, where mobility is hampered not only by distance but by water; lack of emergency infrastructure; and by the prohibitive expense of self-funding travel. The Review recommends that the Commonwealth, state and territory governments work together to establish a nationally consistent travel grant for people experiencing violence in remote and very-remote areas, to help prevent the escalation of violence.

| Recommendation 9 |

|---|

The Commonwealth, through the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and with state and territory governments, to expedite a needs analysis to determine unmet demand in DFSV crisis response, recovery and healing (excluding police), with the view to develop a pathway to fund demand. This should take into consideration the needs of different groups of women and children and the demand for targeted and culturally safe responses, such as ethno-specific services and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled organisations, with a particular focus on remote communities. More immediately, there should be a significant funding uplift for:

|

Apply a prevention lens to crisis response and recovery

”I was distraught as I did not know the area and didn’t know what I would do on my own at totally a new place that’s absolutely unknown to me for two weeks in a motel. During those two weeks I was in so much depression and chaos. Most women would have gone back in the situation ...”

– Adya, victim-survivor137

“Joanne described her time at the refuge as, ‘the best support and someone to help you 24/7 when you are feeling hopeless. It gave me time to heal, get myself in a good place to have my kids back and allowed me to have parenting after family violence sessions, counselling every week and they [the practitioners] also helped me reconnect with employment so I could save towards reunification with the kids and getting our own place.”

– Joanne, victim-survivor138

“Aboriginal services are working with women who have complex and often multigenerational trauma and require long term and specialised support for themselves and their families.”

– Djirra, Family Violence Prevention Legal Service139

The Review acknowledges that specialist DFSV crisis response and recovery services are critical to the prevention landscape. Caseworkers, crisis line counsellors and specialist refuge workers act under enormous pressure, and during times of heightened crisis, to prevent homicide and DFSV-related suicide. These services are experts at managing safety and risk and work to extract victim-survivors from life-threatening situations, often calling in assistance from disparate systems to coordinate rescue missions across the country, including complicated extraction operations from Australia’s most remote areas. For many victim-survivors, this assistance is literally the difference between life and death.

The Review recognises that one of the most predictive factors of future victimisation is prior victimisation. A consistent crisis and recovery response that removes barriers to escaping abuse; helps victim-survivors to navigate a complex web of systems post-separation; and improves their economic security can protect them against re-victimisation, either from their current abusive partner, or a partner in the future.

The Review notes with concern that, over the past decade, there has been an increasing reliance on motels to provide crisis accommodation for women and children fleeing violence.

As the number of refuge beds have been eclipsed by escalating demand, however, motel stays have become long and protracted. In 2024, the average stay is now 14 nights, with the number of women and children accommodated every night reaching more than 200. This leaves many victim-survivors (up to 50 per cent) with no choice but to make an unsafe exit, and even return to the dangerous person from whom they just escaped. Important to note, the vast majority of these clients are facing elevated homicide risk - 90 per cent have been strangled – and the majority are reporting active suicidality (52 per cent in April 2024). More than 90 per cent of callers to Safe Steps family violence crisis line in Victoria who are rated as ‘serious risk requiring immediate protection’ are placed in motels.140

The Review recognises that, for victim-survivors at high risk, hotels and motels are not just inadequate, but dangerous. Unlike specialist refuges, there is no security, and with surveillance devices now commonly used by perpetrators to track their victims through their phones and cars, there is increased risk that perpetrators will be able to find and easily access victims at these insecure locations. Here the Review notes that these accommodation options are especially unsuitable for victim-survivors with disabilities or other health conditions.

To address the dangerous and counter-productive use of motels, Safe Steps created the Sanctuary model – a wraparound service that accommodates women and children for three weeks, while they wait for a space in refuge.

The benefits of this approach are immediate. What’s more, the Review has heard that this specialist accommodation service is actually more cost effective than accommodating victim-survivors in motels. The Review notes that this is low-hanging fruit for governments and recommends that state and territory governments transition from the dangerous and counter-productive reliance on motels to ensure that women and children have access to specialist DFSV accommodation when they need it.

Women’s and Girls’ Emergency Centre ACCESS program

The ACCESS program is a free personalised mentoring program to support women to identify their strengths, build self-confidence and set goals for the future. It is a 3–6-month program that supports women and non-binary people aged 18+ who would like free mentoring either in-person or virtually. ACCESS mentors are women and non-binary people looking to support other women and non-binary people to build on their goals.141

Further, the Review notes that the circuitous route towards safety, independence and freedom requires long-term case management with specialist DFSV workers who know how to navigate these systems. Managing DFSV related processes alone can lead to debilitating stress and increased trauma and is made even more complex for victim-survivors who have limited English, or face communication impediments connected with disability.

As the Review notes in Recommendation 5 (Children and Young People), vouchsafing recovery for protective parents and their children is not only essential for immediate safety, but also vital for interrupting intergenerational violence and disadvantage, which can prevent future victimisation and perpetration in the next generation.

Essential to this recovery is safe housing. DFSV is the leading cause of homelessness for women and children in Australia, and victim-survivors accounted for 42 per cent of Specialist Homelessness Services clients in 2020-21.142 Research from Safe and Equal shows that the vast majority of family violence services in Victoria commonly see repeat clients, and a lack of affordable housing is a key reason why victim-survivors return to live with their abuser.143 The Review heard that provision of sustainable, affordable and accessible housing in initial contact with victim-survivors is an economic imperative for governments and the most significant impediment to keeping victim-survivors safe. Without this investment, especially in regional and remote areas, prevention will be undermined and cycles of poverty, violence and disadvantage will continue or even worsen.

Sanctuary model

In October 2023, SafeSteps Family Violence Response Centre, Victoria began the 12-month Sanctuary Pilot Program. This program provides short-term supported crisis accommodation to victim-survivors of domestic and family violence. At Sanctuary, Safe Steps staff provide 24/7 intensive face-to-face crisis support to residents, including children, until they can be referred to appropriate longer-term accommodation, including women’s refuges.144

At the core of the Sanctuary service model is a commitment to providing therapeutic, culturally safe, accessible, and tailored support to meet the individual needs and circumstances of all residents, including children. It aims to provide wrap-around support for residents, including through intensive, face-to-face case management support and a range of in/outreach services.145

In contrast to motels, Sanctuary offers a safe, supportive environment that allows residents to build protective factors against domestic and family violence and, in doing so, increase the likelihood of positive longer-term outcomes. The Sanctuary pilot site is located in Melbourne’s northern suburbs and includes seven fully-furnished, self-contained apartments and several large shared spaces, accessible for a range of ages and cultures. Since the pilot commences, the site has provided support to more than 200 victim-survivors.146

Sanctuary is the only supported crisis accommodation model of its kind in Victoria and addresses a critical gap in the service system for people escaping domestic and family violence.147

| Recommendation 10 |

|---|

The Commonwealth and state and territory governments to apply a prevention lens to the resourcing and delivery of crisis response and recovery services. This includes through:

|

Activate the health system

1 in 5 women who experienced violence from a current partner sought advice or support from a GP or other health professional.148

As identified by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Review similarly recognises the largely untapped prevention potential across the health system.149 Health professionals have contact with patients across the life course and, in particular, engage intensively with women at key high-risk periods for abuse onset and escalation, particularly during pregnancy and following childbirth. Older people vulnerable to elder abuse also frequently attend GPs and, in the context of coercive control and isolation, those health professionals may be their only external source of support.150 This is also especially relevant for communities who may not be well served by specialist DFSV services, particularly patients in same-sex and transgender relationships. Evidence indicates that people who use violence are also far more likely to engage and disclose to health services than any other service, including a specialist service.151

Accordingly, the Review concludes that health ministers must prioritise upskilling and resourcing the health sector to identify and respond appropriately to DFSV, so that they have the confidence to broach the subject with patients who may be experiencing or perpetrating violence, as well as the skills to respond to disclosures in a trauma- and DFSV-informed way. As the WHO recommends, this is a key step to “address violence and its consequences and prevent future violence.”152

DFSV and pregnancy

Around 34,500 women reported experiencing violence from a current partner while pregnant and 325,900 reported experiencing violence from a previous partner during their pregnancy.153

Reviews of child death cases in Australia show that amongst other factors, a father’s violence towards the mother during pregnancy significantly increases risk.154

The Review heard that key intervention sites for DFSV are located across general practice, antenatal clinics, community child health, mental health and emergency departments. When healthcare professionals fail to identify DFSV, or respond to disclosures with victim-blaming sentiments, however, the impacts can be fatal. Coroners have repeatedly identified that healthcare professionals lack the adequate skills and capacity to respond to DFSV. Here the Review notes that Victoria’s State Coroner recently reiterated this longstanding concern, stating that “without mandated family violence training, a portion of GPs will remain unskilled and ill-equipped to respond to patients’ disclosures of family violence.”155

A review of 72 studies, conducted by the Safer Families Centre, identified personal and structural barriers that got in the way of health practitioners responding to DFSV.156

The top three personal barriers were:

- 'I can’t interfere': this highlights the belief that domestic abuse is a private matter and practitioners fear causing harm by intervening.

- 'I don’t have control': this illustrates that practitioners feel frustrated when their advice is not followed.

- 'It’s not my job': this illuminates the belief that addressing domestic abuse should be someone else’s responsibility.

The top three structural barriers were:

- Working in suboptimal environments: practitioners are frustrated with the lack of privacy and limited time they have with patients.

- Lack of system support: there is a lack of management support and inadequate training, resources, policies and response protocols.

- Impact of societal beliefs: there can be a normalisation of victim blaming, including myths that women will lie about experiencing violence or that domestic abuse only happens to certain types of women.

The Review heard that child and adult safeguard training should be considered a necessary, life-saving requirement, on par with the mandatory requirement for training on CPR. The Review therefore recommends a consistent approach nationally to mandating DFSV training for two priority healthcare categories, being doctors in general practice and psychologists, developed in collaboration with the Royal College of General Practitioners.

The Review notes that opportunities for identification and intervention are especially critical for First Nations women and children in remote areas, where they are 24 times more likely to be hospitalised for domestic violence as people in major cities.157 The need for a safe and culturally sensitive response is therefore especially vital and can be the difference between life and death.

To equip health professionals to respond more effectively, health ministers should consider expanding the Readiness Program, run by Safer Families: a national training program for primary care providers (including GPs, community health and Aboriginal Medical Services) to recognise, respond, refer and record DFSV using a trauma and DFSV-informed approach. This is a flexible, multifaceted training program that assists healthcare professionals to improve identification and risk assessment; respond to disclosures with active listening and non-judgment; improve understanding of how DFSV impacts children; provide more appropriate support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, migrant and refugee groups and older people; and increase the timely referral of women, men and children affected by DFSV.

Training and skills, however, are not sufficient. GPs must also be given the time to respond to the additional needs of their patients. Evidence indicates that a significant structural barrier is the frustration that practitioners felt with the lack of privacy and limited time they had with their patients.158 To address this, the Review recommends that the Commonwealth Government creates a specific Medicare item number for GPs to spend extra time with patients affected by DFSV. Here the Review notes that any steps in this regard would need to be accompanied by privacy measures.

In addition to upskilling healthcare professionals more broadly, the Review recommends that particular attention and resourcing be given to developing DFSV specialisation across the alcohol and other drugs (AOD) sector, and to facilitating cross-sector collaboration. This kind of intervention is long overdue and holds enormous potential for reducing the recurrence of violence; for intervening more effectively with people using violence; and for preventing further harm to children.

The Review further recognises the potential for greater cross-sector collaboration between specialist DFSV services and the AOD sector, to enhance the AOD sector’s responsiveness to DFSV, and ensure that victim-survivors and people using violence can access specialist DFSV assistance. State and territory governments should also ensure that mental health and AOD services are represented on multi-agency risk management panels.

AOD and users of violence

International studies suggest that 30–40 per cent of men participating in AOD interventions are perpetrators of DFSV and/or of sexual violence outside of the context of intimate relationships.159 Crime statistics show that perpetrators of DFSV who abuse substances, especially alcohol, are more likely to inflict serious injury.160 A high percentage of men attending MBCPs also present with substance abuse issues, which can impede their ability to remain engaged in programs.161

Women who access DFSV supports are also more likely to experience AOD issues, sometimes as a coping mechanism.162 Parental substance abuse is one of the leading contributors to child removal, aside from family violence, meaning that intervening through an FDSV-informed lens is an essential protective mechanism for children.163

Activating health professionals to become first-line responders to DFSV is a national endeavour requiring substantial investment and coordination across governments and government departments. Just as important is activating a DFSV lens across health and broader equity policies, such as the Commonwealth’s Ten Year LGBTIQA+ Health and Wellbeing Action Plan, so that DSFV is recognised in health interventions relevant to diverse and intersecting communities. This includes LGBTIQA+ communities, people with disability, older Australians, people in regional and remote areas and people from migrant and refugee communities. Here the Review notes that, if Australia is to continue to draw on a public health approach as one of the multiple frameworks that can help to prevent DFSV, as discussed at Recommendation 4, it is particularly crucial that the health sector itself steps squarely into this picture.

Wuchopperen Health Justice Partnership

Wuchopperen Health Service, a community controlled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Service in Cairns, partnered with LawRight to form the Wuchopperen Health Justice Partnership. The Partnership grew from an on-site weekly legal clinic to provide two full-day, on-site clinics per week to Wuchopperen clients, deliver free legal advice, referral and casework (civil matters only).

Donella Mills, former managing lawyer at LawRight and Chair of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, spoke to the National Indigenous Times in 2021 about the Partnerships establishment stating, "I kept seeing this missing link, we were talking about family wellbeing, child protection, youth detention, we were talking about issues around chronic disease and I just kept thinking how can we be delivering services when we are not connecting people to legal representation? ... Our people will go to their ACCHO [primary health care service] and tell their doctor about all of their concerns because the trust is there. The trust is not in the legal institution".164

Campbelltown Emergency Domestic Violence Pathway

In Sydney, Campbelltown Hospital, Macarthur Women’s Domestic Violence Court Advocacy and local police have developed an innovative partnership and domestic violence pathway. This pathway requires police to take any person with an injury or suspected injury from non-fatal strangulation, a choking incident or head injury in the context of DFSV to Campbelltown Hospital Emergency Department. There is a direct phone line and separate intake process to ensure these women are seen quickly and are taken to a safe space designated for this purpose, away from the hustle and bustle of the Emergency room.

Benefits include of this partnership include:

- Medical evidence to support charges;

- Immediate safety assessment for the victim and health needs addressed;

- Access to trauma-informed medical care;

- Link with DFSV services to support family and prosecution;

- Fast track to medical attention; and

- No requirement of police to stay, hospital has process to help get individual home. 165

| Recommendation 11 |

|---|

The Commonwealth and state and territory governments to activate the health system and workforce as a key prevention lever. This should include:

|

Being smarter about responses to people using violence

Smarter interventions with people using violence can function as a vital lever for preventing escalation and future harm. The Review has highlighted the prevention potential in developing and promoting healthy masculinities, as well as in activating health sectors to identify abusive behaviour and intervene early. To prevent violence from escalating however, we must also apply a prevention lens to accountability and ensure that we are leveraging the prevention potential in every interaction along a spectrum of interaction.166 In particular, evidence indicates that a window of opportunity exists in the initial stages of justice system contact which, if leveraged appropriately by police and legal practitioners, can improve understanding of court processes and reduce risk, including by addressing immediate support needs.167 This is a clear opportunity to reduce risk and prevent the likelihood of further escalation and violence.

Research indicates that when people using violence have limited understanding of protection orders; receive little to no advice or information prior to an order being made, or have little capacity to absorb what is occurring, this raises the risk of them breaching the order.168 As respondents usually attend court having had minimal support or advice, few may be in the position to make decisions or properly understand the content or consequences of protection orders.

The experience of the legal process itself can also be more important to people than the outcome, with research indicating that people are more likely to view an outcome as valid and comply with this outcome if they perceive the process as fair.169 Research shows that procedural justice throughout the legal process can also maximise engagement with MBCPs when completion of a program is ordered.170

Victoria Legal Aid has developed a specific Model to support duty lawyering across particular Specialist Family Violence (SFVCs) in Victoria. The Model’s activities combine to:

- increase the provision of quality information on legal assistance and court processes;

- increase duty lawyer resourcing across SFVCs;

- provide training and support to lawyers focused on trauma-informed and non-collusive practice, assessing and responding to broader legal needs and negotiating outside court;

- improving support for non-legal needs through the creation of new, dedicated roles, being Information and Referral Officers (IROs) based at each of the relevant sites; and

- improving cultural competency through the creation of dedicated Aboriginal Community Engagement (ACE) officers based at specific locations.

An interim evaluation of the Model found that the non-legal roles were making a real and particular difference to people’s experience at court, providing people with additional help through support and referrals to legal and non-legal services like housing, health and community supports.171

Further, people using violence may have complex needs which have contributed to or escalated their use of DFSV, such as mental ill-health, substance abuse, unemployment or insecure housing, which often go unaddressed. When perpetrators are removed from the home, a lack of stable accommodation may lead them to return to their family or they may present to a first court appearance dangerously heightened, having spent the intervening days between police contact and court attendance living in their car or in unstable accommodation.172 Alternatively, people using violence who have been excluded from the home may be living with extended family or elderly parents, which could put these family members at risk.

The Review recommends that state and territory governments look to current models that leverage early points of justice system contact as a way of preventing future violence and abuse. The Review also recommends that states and territories, with the support of the Commonwealth Government, explore specific investment in crisis and short-term accommodation for people using violence who have been removed from the home.

Research shows that interventions which are designed to achieve ‘perpetrator accountability’ were always intended to be situated within a coordinated community response – including within a ‘perpetrator intervention system’ that is equally accountable to victim-survivors and their priorities for what safety means to them.173 Coordinated community responses which work together to hold people using violence accountable and victim-survivors safe include the Gold Coast Integrated Response, in which MBCPs, specialist DFSV women’s services, local health services, police and Corrections share information to respond and manage dynamic risk.174

The Review also recognises the substantial role played by Men’s Behaviour Change Programs (MBCPs). Here the Review acknowledges that these programs were originally designed and intended to operate as a coordinated community response, but too often are forced to operate in disconnection from other services. This is despite being expected by policy and funding arrangements to carry responsibility for a man’s risk alone.175

While MBCPs are a core component of Australia’s current intervention strategy and are frequently cited as equating to ‘perpetrator accountability’, the Review also acknowledges that the availability of these programs is often scarce. Further, few are specifically designed or resourced to work with people using violence from diverse communities or with intersecting needs.

The Review also heard, and evidence indicates,176 that there is variable quality and capability across MBCPs, with programs and practitioners calling for further work to identify and build what constitutes best practice. Practitioners told the Review that MBCPs need to be appropriately resourced to address the wide range of issues which can contribute to or escalate violence and inhibit progress towards being a safer man. This may include mental ill-health, substance misuse, past and childhood experiences of trauma, gambling harm and housing and financial insecurity. The Review notes that, while these issues can all act as barriers to change, harm can also be compounded if these issues are addressed by practitioners who do not apply a DFSV-informed lens.

The Caledonian System

The Caledonian System is an integrated approach – for men aged over 16 with a conviction – to address men's domestic abuse in Scotland that adopts a comprehensive risk management approach and provides services to men over an extended period of two years, including individual, group and post-group work; support, safety planning and advocacy and liaison with other services to women; and support and advocacy for children.

The Review also heard the need for investment in programs that are culturally safe for men from First Nations and migrant and refugee backgrounds, with an additional need for supply of programs for people from LGBTIQA+ communities, as well as for people with cognitive or intellectual disability or other complex support needs.

Research released by ANROWS demonstrates that partner or family safety contact is often the most crucial component of MBCP work. This is because it often connects victim-survivors to their first source of support, while also providing a crucial reality check in relation to men’s self-reported behaviour throughout their program participation.177

Importantly, the Review recognises that programs wish to be supported as part of a coordinated community response, as their design originally intended. Just as vital to acknowledge, victim-survivors remain the primary focus of these programs. Evidence indicates that partner or family safety contact can be the most powerful intervention offered by these programs, making this a component that needs to be resourced.178 The Review recommends that the Commonwealth and state and territory governments undertake immediate work to improve the supply and capability of these programs across a range of settings to enable increased engagement and retention. Resourcing should take into account the need for these programs to function as part of the overall specialist response to DFSV, rather than being seen as a separate sector with different objectives, which has never been the case.

The Review heard about a range of programs, including:

- The Changing Ways program in Victoria seeks to work with adults who pose a serious risk of harm to victim-survivors. Delivering intensive multi-agency intervention and individual behaviour change work, the program also works intensively with victim-survivors. Being delivered across three sites, this includes at an Aboriginal-led service, Dardi Munwurro, where practitioners are working to address the complex needs of people using violence, including disability, housing, substance use, mental health and justice and statutory intervention.179

- The Wuinparrinthi program is a culturally appropriate youth prevention program for Aboriginal male adolescents who have displayed violent behaviour or are identified as being inclined towards violent behaviour. Young people engage in the program for 6 months, with the aim to mitigate the risk of violent behaviour through awareness and education about positive relationships, coercive control, anger management, positive choices and preventing violence.180

- Futures Free from Violence (FFFV) offers women, trans, and gender diverse people who have used force and/or violence in family and intimate partner relationships the opportunity to work towards change in both a supported group and one-to-one therapeutic environment.181

- Motivation4Change uses an inLanguage, inCulture delivery model to address the significant barriers migrant and refugee men can face when engaging with mainstream family violence services. It combines one on-one case management and group sessions with an understanding of the migration journey, language, culture and faith into the program, using facilitators and other participants of a similar cultural background.182

| Recommendation 12 |

|---|

The Commonwealth and state and territory governments to take targeted efforts to address the significant gaps in responses to people who use violence. This should include:

|

Better risk assessment, decision-making and multi-agency approaches

The Review notes that a significant inhibitor to preventing DFSV and homicide is the lack of a nationally consistent approach to assessing harm and risk, as well as to managing safety. Recent homicides have highlighted an urgent need for stronger, more comprehensive and more consistent risk-assessment and intervention models to support decision-makers to identify, assess and then manage risk more effectively. This is critical for managing victim-survivor safety needs and for preventing escalation of harm. These frameworks can also uplift capability across workforces, including police, court staff, the judiciary, child protection and corrections, wherever people are making decisions which should be determined by DFSV-informed considerations. This includes giving visibility to the fact that not all decisions are currently made by people in positions of judicial authority, as the community might otherwise expect.

The Review recommends that Commonwealth and state and territory governments work together to develop greater national consistency in risk assessment. This should be developed in relation to adult victim-survivors, adults using violence and children and young people as victim-survivors in their own right.

Case study

“Maggie presented to The Orange Door seeking family violence support. She has a cognitive disability, and in her initial risk assessment, Maggie reported that her partner Stephen was mean to her dog, and that he would take the dog outside and tie him up. This was noted in her original referral report with no further context.

Due to her disability, The Orange Door referred Maggie to a private practice family violence consultant. Maggie had a number of sessions with the consultant, where the consultant could build trust and was able to take the time and find ways to communicate appropriately with Maggie.

During the fourth session with the consultant, it was established that the dog was actually an assistance animal for Maggie, not just a family pet. The consultant also elicited that when Maggie said Stephen was ‘mean to the dog’ and being ‘tied up’, he was actually tying the dog upside down by its feet and hitting it. Maggie also revealed that this was often in response to Maggie refusing demands for sex, or to get her to agree to sex with the threat of hurting the dog.

This information changed the risk assessment of the level and types of violence against Maggie significantly. Had the consultant not developed the shared communication understanding and taken the extra time with Maggie, she may not have been referred to the appropriate supports needed to recover from her family violence experiences.”183

Any approach should be culturally-informed and responsive to how risk presents for different people and within particular communities, with a particular emphasis on preventing the potential for misidentification of victim-survivors and associated systems abuse. This is to ensure that the person most in need of protection is accurately identified at the outset, and so that the harm of misidentification is avoided. Particular focus should be given to preventing misidentification in risk assessment in relation to people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, refugee and migrant communities, LGBTIQA+ communities, and people with disability.184

Risk assessments are only effective, however, when the people conducting them are able to make safe and DSFV-informed decisions. In turn, safe decisions cannot be made without access to the right information. Information sharing regimes – where properly resourced and supported – can improve risk assessment, particularly where information about the person using violence would not otherwise be available.

The Review recommends that governments improve operational information sharing across and within jurisdictions to support consistent approaches to risk assessment. The information sharing scheme could be modelled on the Victorian Family Violence Information Sharing Scheme, which the Review heard from frontline services is of particular value, or could leverage the capacity and capability of the National Crime Information System (NCIS), described below. An information sharing scheme could also enable the registering of family court orders, family violence protection orders, child protection orders and other information that is relevant to assessments of risk.

Victorian MARAM Framework & Information Sharing Scheme

The Family Violence Multi-Agency Risk Assessment and Management Framework (MARAM) ensures that services are effectively identifying, assessing and managing family violence risk. The aim of MARAM is to increase safety and wellbeing by ensuring that relevant services can effectively identify, assess and manage family violence risk. The Framework has been established in legislation, meaning that organisations that are authorised through regulations, as well as organisations providing funded services relevant to family violence risk assessment and management, must align their policies, procedures, practice guidance and tools to the MARAM Framework.185

What is the NCIS?

The National Criminal Intelligence System (NCIS) connects data from different Australian law enforcement agencies, providing cross-border secure access to policing information and criminal intelligence. The NCIS is a join project led by the Australia Criminal Intelligence Commission with Australian police agencies and the Department of Home Affairs.

Each Australian law enforcement agency uses different systems for their day-to-day policing activities. By enabling cross-border information sharing, the NCIS enables police to access all available information about risks, details of entities, events of interest and a person’s history.

Importantly, the Review also recommends greater awareness, and use, of the NCIS, as noted above. This could include consideration around careful expansion of access to certain professional cohorts, as well as work to align state and territory systems to enable accessibility and functionality.

The Review heard, and evidence supports, that there is a pressing need for greater collaboration and cross-agency responses to DFSV, especially for policing. The benefits of this approach have been evidenced in pilots and programs in various states and territories. Co-responder models involving collaborations of DFSV specialists with police, for example, can reduce the risk of misidentifying the person in need of protection; provide more consistently safe responses to victim-survivors, including by involving other supports such as interpreters; assist in identifying evidence to support charges; support police to respond to escalating demand, and enable the sharing of expertise and skills.

Misidentification

ANROWS funded research defines ‘misidentification’ as situations where the person experiencing DFSV or most in need of protection is wrongly taken to be the person perpetrating violence (the ‘predominant aggressor’) and the person perpetrating harm is wrongly identified as a person experiencing violence or as being most in need of protection.186 An examination of data related to Women’s Legal Service Victoria clients indicated that 10 per cent had been misidentified, with 5 out of 8 clients experiencing abuse during the incident where they were identified as the ‘primary’ aggressor, which included threats, physical violence, and restraint.187 This echoes findings from a University of Melbourne review of Family Violence Reports from December 2015 to December 2017, where 48 per cent of reports where a woman was listed as the respondent were found to involve misidentification.188

Far from an inadvertent outcome, ‘misidentification’ may be the deliberate outcome of a man’s weaponisation of the system against his female partner. Alternatively or additionally, it may be the direct result of profiling and racism by statutory systems.189 This is reflected in Victoria Police data which shows that, in 2020, close to 80 per cent of Aboriginal women named as a respondent in police Family Violence Reports had been recorded as a victim in the last five years, compared to nearly 60 per cent for all female respondents.190

As the Queensland Women’s Safety and Justice Taskforce found, co-responder models enable a specialist DFSV response to accompany police intervention, as well as for ‘warm referrals’ to services and supports for both victim-survivors and people using violence.191 By working alongside and in consultation with different disciplines, police and other DFSV responders can provide more holistic and wrap around responses to victim-survivors, including with the support of interpreters where relevant, while also developing capability. The Review recommends that state and territory governments introduce and expand multi-agency responses, including police co-responder models, underpinned by an appropriate impact evaluation framework.

Investment in collaborative responses should prioritise workforce development and capability uplift, as well as psychological and cultural safety for practitioners working in cross-disciplinary models. It should also support ongoing risk assessment through risk review meetings across policing, specialist support, perpetrator response, child protection and, where relevant, corrections. The Review also recommends that state and territory governments adopt evidence-based focused deterrence models, ensuring that such models are not limited to a policing response, but also include the offer of community-sector support, where appropriate.192

Supports and co-responder models should urgently be made available at access points through Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-based services, with immediate investment in collaborations such as High Risk Teams and community justice panels, particularly in remote communities such as the Torres Strait.

Further considerations include ensuring that co-responder models or co-locations account for cultural safety – avoiding co-location in police stations, noting that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, LGBTIQA+ communities, people with prior criminal justice system contact, those involved in sex work, and those with uncertain immigration status, may be hesitant reporting any experiences of violence to police, particularly sexual violence. This means that co-responder models should be made available in services which support these diverse cohorts.

Co-responder models

There are a range of co-responder models, including:

- co-responder models or multi-disciplinary centres in which practitioners from different disciplines are co-located or otherwise inform each other’s practice through regular secondary consults or flexible arrangements;193

- where practitioners (for example, Child Protection) are available to provide secondary consults in a legal environment, such as the Family Court;194

- where specialist DFSV and MBCP practitioners work in collaborative teams within Child Protection;195 and

- community justice panels in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, which help to inform appropriate legal decision-making.

Alice Spring co-responder model

In June 2024, a new co-responder model trial in Mparntwe, Alice Springs commenced with the aim of offering greater support to victim-survivor of domestic and family violence and providing earlier intervention for users of violence.

This initiative is being run between the Department of Territory Families, Housing and Communities, Northern Territory Police, and specialist DFSV organisations, Women’s Safety Services of Central Australia (WoSSCA) and Tangentyere Council Aboriginal Corporation.

Following the Police response to domestic and family violence incidents in Alice Springs, three specialists from these organisations will work with victim-survivor to provide support and encourage perpetrators to partake in behaviour change programs.

These specialist support workers will be based at the Alice Springs Police Station and will be able to provide advice to police in real time.

It is hoped this new model will strengthen the integrated approach required by multiple agencies to address DFV and will see the workers provide specialist assistance and advice to Police in relation to DFV.196

In addition to expanding the development of alternative reporting options that are not reliant on contact with police, the Review recommends that the Commonwealth and state and territory Governments urgently invest in capability uplift for community-based or cohort specific services to respond appropriately to disclosures of DFSV, with a particular focus on disclosures of sexual assault.

Forensic examinations

Research in Victoria has identified a significant constraint on the availability of forensic examinations following sexual assault, including assault in the context of family violence.197 This was initially because of restrictions on forensic examiners travelling while ‘stay at home’ orders were enforced during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, victim-survivor who wanted a forensic examination had no choice but to ‘hold evidence’ (i.e. remain in the clothes in which they had been assaulted and avoid washing) while travelling in a police van to another part of Victoria to be examined.198

During this time, many victim-survivor chose not to undergo a forensic examination after a sexual offence – losing the opportunity for forensic evidence to be collected that could inform (and sometimes be crucial to) any future prosecution.199 As at September 2023, the full remit of forensic examinations had not been reinstated, with victim-survivor still limited in the forensic support that they could receive.200

At the other end of Australia, the Review heard that, to undergo forensic examination, victim-survivors of sexual offences in the Torres Strait need to travel to Cairns while holding evidence, leaving their support networks and family and travelling over 800 kilometres via boat and two plane flights or via helicopter. Community members explained that it would be valuable to have a doctor or nurse with the specialist examination skills, or the ability to get instructions over the phone or via technology for a nurse to do the examination, so that the victim-survivor did not have to make the choice between whether or not to leave the islands.

Noting the particularly low reporting, prosecution and ultimate conviction rates of sexual offences, urgent investment should be directed at technology platforms which enable multi-disciplinary, cohort-appropriate and culturally safe forensic examinations.201 Doing so can reduce trauma for victim-survivors, ensuring that they have the option of a forensic assessment without travelling significant distances while ‘holding evidence’.202 It can also ensure that evidence is collected in a timely fashion by specialist examiners; and that local practitioners are supported and upskilled in real time.

The Review further recommends that Commonwealth and state and territory governments consider the Australian Institute of Criminology’s proposal to trial and evaluate domestic violence threat assessment centres, modelled on fixated risk assessment centres for countering violent extremism. These centres could offer a multi-agency approach to information gathering, monitoring and intervention among high-risk offenders during periods of acute risk.

Finally, the Review notes that one of the most crucial sources of prevention potential – particularly for domestic homicides – lies in police prioritising victim-survivor calls for assistance. As such, the Review supports longstanding calls – particularly from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities – for independent oversight bodies for police. Current conduct and complaints systems have been critiqued in various recent inquiries, including the Commission of Inquiry into Queensland Police (which also recommended civilian-led oversight for police).203 The need for accountability is significant, to reduce police-related harm and rebuild trust and confidence in the communities that they serve. The Review recommends that all jurisdictions implement transparent complaints mechanisms for genuinely independent oversight of police that are DFSV-informed, civilian-led and sit outside of police authorities.

North Ireland police accountability model

The Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland (the Ombudsman) is free, independent and impartial and investigates all complaints and allegations made against law enforcement officials in Northern Ireland. The Ombudsman is able to deploy a range of investigative powers and has direct input into the outcomes of cases, while being institutionally independent from the police and free from external influence.204 Scholars have identified the Ombudsman as meeting a range of criteria for the civilian control model.205

Evidence examined by the Review also indicated that decisions regarding the prioritisation of sexual offence investigations also function as a barrier to preventing further offending, given that so many prosecutions do not proceed because of actions at the investigation stage.206

The Review therefore recommends greater public reporting on the rates and timeliness of responses to victim-survivor calls for emergency assistance, as well as the timeliness of police investigation from reporting through to decisions around whether to proceed to prosecution, particularly in sexual offence matters.

This includes decisions around when and why matters were not referred for prosecution, at a de-identified and aggregate level. Greater transparency and understanding around ‘attrition’ patterns – too often misconstrued primarily as the result of decisions of victim-survivor, which evidence shows is not the case – will improve accountability for police and prosecutorial decisions and increase the likelihood that this area will be treated as core police business.207

| Recommendation 13 |

|---|

The Commonwealth and state and territory governments to work together to strengthen multi-agency approaches and better manage risk, with a lens on harm and safety, for victim-survivors of DFSV, including risk of homicide and suicide. This should include:

|

Build a firm foundation for prevention

With the national emergency that Australia currently faces, comes substantial and unsustainable impacts on the DFSV workforce. The Review heard that the burnout rate for specialist DFSV workforces is alarming, with a level of lethality across presentations which staff are not equipped to respond to, especially at such consistent and sustained regularity. In particular, the Review heard that DFSV specialist staff are being exposed to extreme levels of vicarious and direct trauma which, when coupled with chronically low wages and limited psychological supports, are resulting in rapid staff turnover and protracted vacancies. This is particularly pertinent in regional, rural and remote areas, where services are unable to compete with opportunities in metro regions and the private sector, or where community-led organisations are often staffed by community members who require additional supports and considerations not often built into funding agreements.

The Review recognises that more work is required to resource and support the DFSV specialist (including MBCP) and sexual violence sectors – including to unlock their full prevention capacity.208 It also recognises that other workers who frequently engage with people who experience and use violence – including those who work in the health, legal and justice, child protection and education sectors – play a considerable role in identifying and preventing violence. The approach to building the DFSV skills and capacity of these workers, however, is piecemeal across sectors, services and locations.209

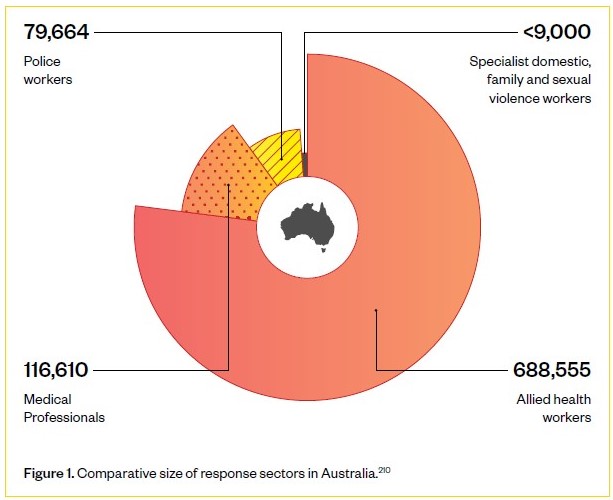

Figure 1. Comparative size of response sectors in Australia.210

To take a sophisticated and well-informed approach to building the specialist sector, the Review recommends that an expert body, such as Jobs and Skills Australia, the Productivity Commission or other appropriate body, undertake analysis of the current and future labour supply for these specialist sectors and provide advice to governments on how to build a sustainable and professional workforce. The Review also recommends that a DFSV National Workforce Development Strategy be developed that covers these specialist sectors, as well as the broader sectors involved in DFSV prevention. This Strategy should focus on:

- Addressing workforce needs and sustainable funding for the specialist sectors, including: workforce attraction, pipeline and retention; training and skills development, including the role of universities and vocational education and training (VET); professionalisation; wages, noting the Fair Work Commission’s gender undervaluation case that is under way; and supervision and management, noting the stressful and traumatic nature of work in these sectors.

- A systematic and coordinated way to build the DFSV skills, capability and qualifications of workers in broader sectors – for example, health, law and justice and education - including through universities, VET and on the job learning.

- DFSV specialist and broader sectors building skills to work with children and young people; First Nations people; people with disability; LGBTIQA+ people; and other culturally diverse communities. This includes supporting workforces in both mainstream and targeted services for these groups.

| Recommendation 14 |

|---|

The Commonwealth and state and territory governments to work together to build the specialist DFSV workforce and expand workforce capability of all services that frequently engage with victim-survivors and people who use violence. This should be done through:

|

Bring sexual violence into focus

The number of victim-survivors of sexual assault recorded by police rose by 11 per cent in 2023, the 12th straight annual rise.211

There are an estimated 50 sexual assaults in residential aged care each week.212

The Review recognises that Australia requires a stronger focus on preventing and responding to sexual violence amidst the wider attention on gender-based violence. Here the Review notes that sexual violence and domestic and family violence often co-occur.

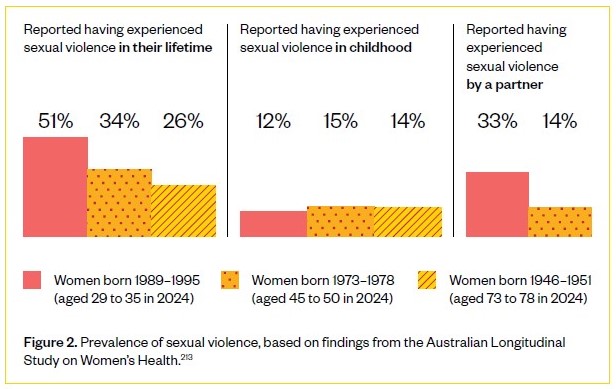

Figure 2. Prevalence of sexual violence, based on findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health.213

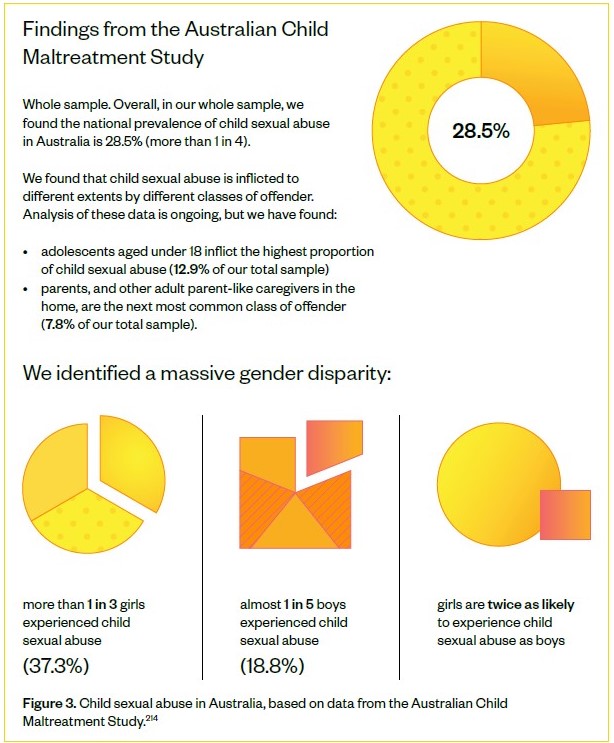

Figure 3. Child sexual abuse in Australia, based on data from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study.214

Equally vital to acknowledge, sexual violence also occurs outside domestic and family settings and intimate partner relationships. As a result of divergent clinical, community and justice responses, however, sexual violence often receives a different response to domestic and family violence in the context of legal and support systems.

Increased reporting of sexual violence over recent years and, in particular, high levels of sexual violence experienced and reported by young women, highlight a need for urgent attention.215 While consent laws have changed and associated education has become more widespread, the challenges of online pornography, deepfakes and other forms of generative artificial intelligence (AI) pose new and significant challenges. The Review recognises that approaches to prevent and respond to sexual violence must continue to evolve to meet the changing environment, especially online and amongst young people.

In light of increased reporting, the Review also heard that the specialist sexual violence sector is struggling with growing annual demand for their services and that, in particular, services gaps exist for diverse communities, for men and boys, as well as for children and young people. The Review also heard about a need for accountability in investigation by police as recognised in recommendation 13; about a particular lack of access to forensic examination, as also noted in recommendation 13; and about a need for a focus on the prevalence of child sexual abuse, including in the context of incest and harmful sexual behaviours by children.

To address this – and in recognition that sexual violence has not received adequate attention in the national policy landscape - the Review recommends that governments further expand and prioritise work on Action 6 in the First Action Plan (2023-2027) of the National Plan. This increased focus should:

- highlight the unique and evolving nature of sexual violence, and the need for prevention approaches and responses to meet these complexities and constant changes;

- include effective and evidence-based ways to teach consent to young people, as well as the dynamic nature of online influences and their impact on people’s experience of the world and sexual behaviour;

- examine the resources needed for the specialist sexual violence sector, and broader sectors including education and health, to respond and meet the needs of victim-survivors more comprehensively, including survivors of child sexual abuse;

- noting the Australian Law Reform Commissions current reference on justice responses to sexual violence, due to report in January 2025, outline justice responses that validate victim-survivor experiences, potentially through processes outside the criminal justice system, such as through restorative approaches, including those based in the community; and

- address the needs of diverse communities and recognise different experiences of sexual violence, including: violence against women with disabilities and older women, including in institutional and residential settings; sexual exploitation of women on precarious visas and the need for greater accessibility to services which provide support for trafficked persons; sexual violence experienced by those working in the sex industry; and sexual violence experienced by First Nations women and LGBTIQA+ people.

A recent study has found that women and gender diverse people working in the Victorian sex industry:

- face increasing financial and immigration insecurity following COVID-19 and, as a result, enduring greater levels of risk in their working and personal lives;

- face increased rates of intimate partner violence, particularly in the form of technology facilitated abuse as well as threats to ‘out’ their occupation; and

- felt unable to access sexual health, justice or sexual assault services.216

The DFSV and justice sectors may struggle to identify modern slavery crimes under the Commonwealth Criminal Code, which means that victim-survivors are not able to access support through the Support for Trafficked Peoples Program, as this relies on referral from (and therefore reporting to) Australian Federal Police. This may include where a perpetrator coerces or deceives a victim-survivor into entering what she thought to be an intimate partner relationship but where the perpetrator has exploited the victim-survivor for financial gain.217

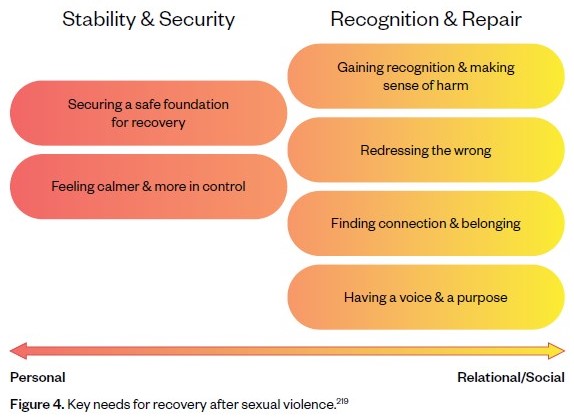

Evidence clearly indicates that the criminal justice system does not support recovery for victim-survivors of sexual violence, with recent research highlighting the key needs for recovery after sexual violence encompassing a gamut of different domains and experiences, including where recovery is impacted by ableism or other forms of discrimination.218

Figure 4. Key needs for recovery after sexual violence.219

This Review notes that this increased focus should align with other national frameworks and plans including the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032, Working for Women: A Strategy for Gender Equality, the National Women’s Health Strategy 2020-2030, Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021-2031, the National Strategy to Prevent and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse 2021-2030, Safe & Supported: The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2021-2031 and the National Action Plan to Combat Modern Slavery 2020-2025. It should also align with forthcoming documents including the standalone national plan for First Nations family safety and a successor to the National Plan to Respond to the Abuse of Older Australians (Elder Abuse) 2019-2023.

| Recommendation 15 |

|---|

| The Commonwealth and state and territory governments should further expand and prioritise work on Action 6 in the First Action Plan (2023-2027) of the National Plan to recognise the full range of sexual violence including where it occurs apart from DFV particularly noting the recommendations from the forthcoming Australian Law Reform Commission inquiry into justice responses to sexual violence. |