On this page

Guiding recommendation: Ensure pandemic support measures include all residents, regardless of visa status, prioritise cohorts at greater risk, and include them in the design and delivery of targeted supports.

The COVID‑19 pandemic confirmed that while everyone faces higher risks and negative impacts during a major health emergency, certain groups of people will experience a disproportionate level of risk and impacts. This may be due to pre‑existing health, social or economic inequities – such as in the case of priority populations – or to employment circumstances or geographic location. Additionally, there may be new challenges arising from the specific features of the pandemic in question, including the population groups more susceptible to severe disease or death.

The pandemic also demonstrated that the Australian Government’s response can have a significant impact on how populations experience a pandemic. For some groups, the actions of the Australian Government during the COVID‑19 pandemic compounded the negative effect on their health and wellbeing.

Women, for example, were more likely to be working in sectors impacted by the public health orders, experienced a greater increase in caring responsibilities and faced a heightened risk of experiencing family and domestic violence.

I had my entire family move back in with me … including my ex‑partner who was abusive and the whole situation was just so traumatising.35

A successful pandemic response requires governments to account for differences across groups in the design, delivery and implementation of responses. It is important that the government response recognises these differences and ensures measures do not exacerbate or create new inequities through exclusions from supports, or ill‑designed policies. In particular, groups most likely to be at risk should be prioritised from the beginning of a crisis to maximise the effectiveness of responses and monitor for any unintended consequences.

As mentioned under ‘Relationships’, the Australian Government progressively established consultative forums for a number of priority populations during the pandemic, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, older Australians, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, and people with disability. These were an important mechanism for the voices of key cohorts to be heard by the Australian Government to inform tailored responses.

Early in the pandemic, the heightened risks that the COVID‑19 virus posed to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were acknowledged. This recognition was underpinned by the knowledge of the widespread health inequities and socio‑economic disadvantage experienced by many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations as an enduring impact of colonisation, and the particular pandemic risks for those living in remote communities.

In partnership with communities, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services and local governing bodies, governments implemented response measures that reflected local priorities and needs. These measures ranged from the design and dissemination of communications to the delivery of tailored health and vaccination services and the lockdown of some remote communities. In doing so, the community‑controlled sector and governments jointly built upon years of work undertaken through the Closing the Gap reforms to ensure that Closing the Gap Priority Reform Areas were factored into all aspects of the response. These strategies helped delay transmission, bought time to build workforce capacity and contributed to better health outcomes, particularly in the first 18 months of the pandemic. These outcomes would not have been possible without the latent strength of the Aboriginal community‑controlled sector that was well positioned to respond to a public health crisis, and the pre‑existing relationships built through work on the Closing the Gap reforms.

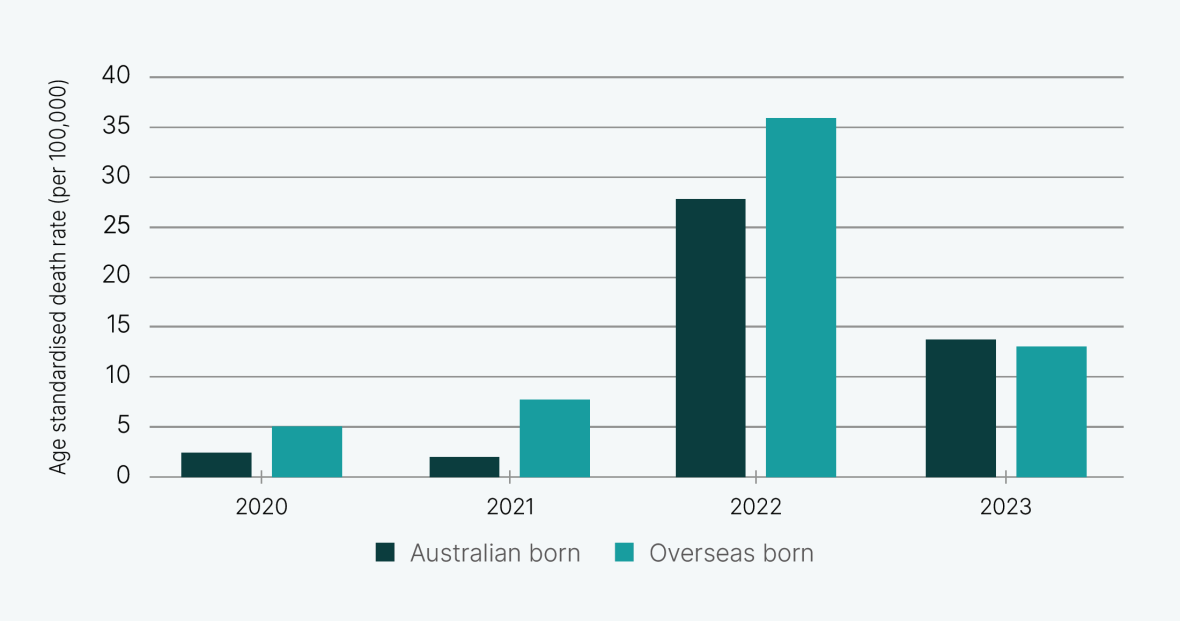

In contrast, the Inquiry found that the additional risks faced by culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities were not sufficiently anticipated, understood or addressed through much of the response. Throughout the pandemic in Australia, CALD people, particularly those born overseas, experienced substantially higher COVID‑19 death rates than the general population (See Figure 4).36 This is all the more alarming given that, in 2019, overseas-born Australians had lower standardised death rates than Australian‑born individuals.37

In addition, the death rate for people born overseas was much higher at particular points of the pandemic: during the Delta wave it was 3.8 times the rate of people born in Australia. There were also significant differences in mortality rates among CALD communities. During the Delta wave, the mortality rate was 80 times higher for people born in Tonga and 47.7 times higher for people born in the Middle East compared to people born in Australia.38

Text description of Figure 4

Bar chart showing the age standardised death rate of overseas born compared to Australian born is higher in 2020, 2021, 2022 and marginally lower in 2023.

Age standardised death rates for overseas born and Australian born people are both higher in 2022 compared to 2020 and 2021.

Despite these figures, there were no data or analyses to determine what was driving this higher risk and what policies might mitigate the higher levels of mortality. For example, we did not have data to understand the underlying barriers that might be contributing to the higher death rate. Were some CALD communities also over-represented among COVID‑19 hospital admissions, seeking health care later than other populations? Without this information it was not possible to identify how risk of infection, disease or inadequate care may have contributed to the disparity in mortality.

Ensuring everyone is looked after in a pandemic can help reduce pressure on health and other services, maximise the achievement of health objectives and limit unintended consequences. The decision to exclude international students and other temporary visa holders from certain supports, including income support measures, reflected the continuation of prior policy settings but was not appropriate for a pandemic.

Many young temporary residents experienced considerable hardship during the pandemic as a result of being unable to work during initial lockdowns and, without access to income support, became increasingly reliant on food relief and financial assistance from universities, charities and state governments.40 This placed unnecessary stress on these service providers during a period of already high demands.

Other temporary residents were forced to leave Australia, which contributed to labour shortages as Australia transitioned out of the pandemic. Later in the pandemic, some supports were provided regardless of residency or citizenship status, but this did not reverse the damage caused by those earlier exclusions.

They didn’t consider us as human. We’re just some aliens who don’t belong here. No rent help, no food help, not even a single penny. I have been surviving with my superannuation money till now. Thank god they at least decided to give it.41

Inequities in impact have continued after the pandemic was declared over, as witnessed through the impacts of long COVID and the ongoing increases in poor mental health being experienced by children and young people. Responding to these issues appropriately has been hampered by the lack of data on impacts, and while the Australian Government has provided some additional resources for research into long COVID, there remains a lack of strategy and of a coordinated approach.

Lessons for a future pandemic

During a pandemic, the Australian Government must ensure that everyone is looked after, regardless of ethnic background, visa status, health status or disability, age or gender. Where there are groups of people with pre‑existing vulnerabilities, government response measures should be tailored to take these into account.

At‑risk groups can be particularly affected by a lack of recognition of the risks they face and any delays in developing response measures to address these risks. Effective mitigations are complicated by the fact that responsibility for the relevant policy areas is often shared across departments. Noting that plans will most likely need to be updated to reflect the specific nature of a pandemic, the extent to which up‑to‑date plans are already developed will determine how responsive and effective tailored measures are, and the effectiveness of coordination between government departments.

Maintaining data systems that facilitate the assessment of differential risks and impacts facing different groups is critical to ensuring that priority groups are identified early in a particular pandemic, issues are identified quickly and disparities can be mitigated or addressed. If well established at the start of a pandemic, such intelligence systems can also facilitate ongoing monitoring and mitigation of the long‑term impacts of a pandemic.

Involving priority populations in the design and delivery of response measures, including communications, is critical for a successful response. For some groups, this will involve using community consultation, partnerships and co‑design. For others, advisory structures that enable input and feedback regarding the unique experiences and needs of populations to be communicated directly to decision-makers will be most appropriate. Representatives of priority populations should also be involved in leading the development and delivery of tailored communication materials.

Plans to transition out of a pandemic should also include provisions for priority populations. In particular, the impact of pandemic response measures being rolled back should be considered. Changes in risk conditions should be communicated so people understand how the threat is abating. Additionally, changes should be implemented gradually so that specific groups do not face increased health risk or fears associated with this risk.

Back to topImmediate actions

In order to support equity in a pandemic response, the Inquiry has identified the following immediate action to be completed over the next 12 to 18 months:

- Proactively address populations most at risk and consider existing inequities in access to services (health and non‑health) and other social determinants of health in pandemic management plans and responses, identifying where additional support or alternative approaches are required to support an emergency response with consideration for health, social and economic factors.